- Home

- Cara Lopez Lee

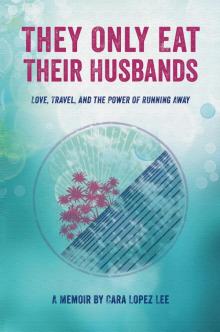

They Only Eat Their Husbands

They Only Eat Their Husbands Read online

Praise for

They Only Eat Their Husbands

“Lee writes candidly about her adventurous—and sometimes tumultuous—journey through life. Her vivid prose draws you into that journey. Her passion makes you want to stay for the ride.”—Valorie Burton, author of What’s Really Holding You Back?

“With an open heart, Cara Lopez Lee relates her round-the-world journey to self-discovery with the unabashed, dazzling honesty of a good friend telling you her innermost secrets over a cup of coffee. The backdrop of intriguing cultures and landscapes further enriches Lee’s bold memoir, They Only Eat Their Husbands.”

—Rose Muenker, winner of the Society of American Travel Writers Gold Award Travel Column

“Lee gets it right about life and love in the Last Frontier in They Only Eat Their Husbands. Her adventures on the road had me laughing out loud with a heart-tugging message we can all relate to.”

—Lauren Maxwell, anchor of CBS 11 News This Morning, Anchorage, Alaska

“Lee takes you on a fun, fabulous adventure—perfect for any woman who wishes she could escape ‘life’ to travel the world.”

—Susan Kim, anchor, Live at Daybreak, today’s tmj4, Milwaukee, wisconsin

“Lee’s ill-advised romances with a cast of Alaskan rogues had me alternately laughing and wanting to shout, ‘No, don’t do it!’ Meanwhile, her descriptions of the unusual people and exotic locations she encountered on her travels made me eager to experience them myself . . . until I remembered Asian rats and European robbers are not my thing.”

—Mark Graham, author of The Fire Theft

“Lee’s compelling personal journey is told with a modesty that downplays the many achievements she has accomplished and the sometimes painful lessons she has learned throughout her life. The pages turn easily with vivid descriptions not only of the places she travels through but of the lovers, friends, and people she travels with.”

—Jeffrey Moore, Producer, Destination Wild, Fox Sports

“A witty and moving story that truly captures the sense of wonder, self-discovery, and adventure that unfolds when one throws caution to the wind and ventures out into the world alone. This is what travel is really all about...experiencing real life through unfiltered eyes, embracing the unknown, challenging yourself, and never losing your sense of humor in the process.”

—Anne Fox, Citizen Pictures, producer Giada’s Weekend Getaways, Food Network

CONUNDRUM PRESS A Division of Samizdat Publishing Group.

PO Box 1353, Golden, Colorado 80402

They Only Eat Their Husbands: Love, Travel, and the Power of Running Away

Conundrum Press edition.

Copyright ©2014 by Cara Lopez Lee.

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For information, email [email protected].

ISBN: 978-1-942280-00-2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014951807

Conundrum Press books may be purchased with bulk discounts for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information please email:

[email protected]

Conundrum Press online: conundrum-press.com

They Only Eat

Their Husbands

Love, Travel, and the Power of Running Away

A memoir by Cara Lopez Lee

A Division of Samizdat Publishing Group

Author’s Note

Although this book is a true account, I’ve taken minor precautions to protect the people who appear in it, and I’ve taken minor poetic license to serve the audience who reads it. To respect people’s privacy, I’ve changed the names of most characters. To further protect a few of those people, I’ve altered minor details of appearance or profession. To streamline the book, I’ve combined a few minor characters, blended a few conversations, and condensed the timing of a few events. All that said, the events and dialogue in this book provide a much more accurate representation of my experiences than you might expect, thanks, in part, to my extensive journals. However, some of the quotes should not be taken as verbatim; rather, they provide my best recollection of what was said or the types of things that were said. Others might recall the events in this book differently, and I respect that. Memory is always colored by individual perception and by time. I don’t profess my memory to be perfect, only that I’ve striven to be honest and fair in sharing it.

For Mom, who opened three doors:

to books, to her home, to the world.

Alaska Escape Plan

Running away is vastly underrated.

I learned that long before I came to Alaska, before I discovered the isolation that comes with the darkness of winter, before I began to contemplate the severe curvature of the globe where I’ve spent nine years living out of sight from the rest of the world. I always believed that people who said running away never solved anything were simply people who stayed put.

When I was a child living in the suburbs of L.A., on the days when I felt that no one cared about me, I packed my little blue suitcase with a toothbrush, a single change of clothes, and a small stuffed lion named Leo and ran away from home, sometimes for hours. I returned only to realize no one knew I’d left.

When I was twenty-six, one night shortly before I left Denver, I had another in a string of arguments with Aaron, the boyfriend I lived with. After the initial shouting died down, I tried to explain all the things he did, and failed to do, that made me feel he didn’t care about me. He crawled into bed, closed his eyes, and listened for a very long time, then said in a calm, cold voice, “Cara, when you keep going on and on and on like that, it makes me think about guns . . . and knives.” He didn’t say another word. Terrified, I fell silent, and waited.

I heard the unmistakable change in his breathing that signaled sleep and tentatively whispered his name. No answer. I grabbed a sleeping bag and a change of clothes and ran away to a friend’s house. I was back before Aaron woke the next morning. Like my family, he never noticed I’d left either.

It was not, I think, unreasonable for me to let my imagination take his threat to its insane but logical conclusion. Once during an argument, Aaron pulled his gun out of the closet, grabbed me, forced the gun into my hand, and urged me, “I can’t take this any more. Just put me out of my misery now. Go ahead, just shoot me!”

I dropped the gun on the couch and pulled away, shaking with fear. “Please stop it! Please! You’re scaring me!”

He rolled his eyes. “Oh, quit making a big deal out of nothing. I was just kidding. It’s not loaded. See?” He picked up the gun and opened the chamber. It was empty.

Usually our arguments were your basic screaming matches. But, once, he shoved me against the wall with his hands around my throat and said, “Don’t push me”; once, he shook me until I could feel my brains rattling inside my skull; and, just once, he threw me across the room, although he was thoughtful enough to aim my body at the bed for a soft landing.

It wasn’t the latent violence that upset me most. It was the insults, always delivered as jokes. One night, when I visited him at the nightclub where he tended bar, he pointed out a sexy young cocktail waitress with measurements of about 36-24-34—compared to my less notable 34-27-36—and said, “If you had a body like that, I’d marry you in a heartbeat.”

Aaron was the funny, friendly, popular guy everybody loved, who would never turn his back on a friend, or stranger, in need. No one knew

what happened between us in private. He told me I was the one with “problems.” Having fewer friends than he did, no outside frame of reference, and no actual bruises, for a long time I believed him.

By the time I realized that, no matter whose problem it was, I had to leave, I’d already begun to rely on him financially. Working part-time as a nightclub DJ and restaurant cashier while finishing college, I was low on ready cash. I felt too humiliated to ask my family for help. In my last semester of school and getting straight A’s, I just wanted to hold out until graduation.

Then, just before I graduated, Aaron was diagnosed with testicular cancer. In my feeble understanding of relationships, this earned him my unqualified forgiveness. How could I stay angry? Bald and puffed up from chemotherapy, with one lonely testicle as lost in its sack as a new divorcé in a king size bed, he was even more difficult to resist than when he’d first turned on his blond, fit, oversexed charm. That he should lose one of his balls was ironic, given his indiscriminate lechery toward other women, marked by such pithy lines as “I’d like to turn you upside down and lick you like an ice cream cone.”

Yet he turned his loss to advantage, tossing a twinkling blue-eyed wink at this or that pretty young thing and saying, “I used to be nuts. Now I’m just nut.” Maybe the joke was lame, but his self-effacing acceptance of the cheap joke life had pulled on him was sincere, and even looking like hell he continued to charm everyone, including me.

But when I began to insist he make a commitment, or at least stop throwing his cigarette butts in the kitchen sink, and he began to insist I move out, or at least stop letting the water puddle outside the shower, the tension grew. It seemed to me I was someone else, the day he dragged me through the living room by the arm, my body knocking over his fuzzy blond furniture along the way, as he screamed his outrage at my inability to drop a subject. God knows what the subject was. I absently worried that my arm might pull out of the socket, but my more persistent thought was, “This can’t really be happening to me—I have a college degree.”

We finally fell to the floor, physically and emotionally exhausted, and he apologized, more or less: “I’m sorry. No one since my ex-wife has ever driven me that far before.”

Later, when I tried to suggest that he had an anger management problem, he yelled, “Don’t give me that! I never hit you.” Technically that was true; he never hit me. I only wished he had; it would have made the choice to leave so much clearer.

In December of 1989, I began making plans to run away for good. It had been more than a year and nearly seventy-five rejection letters since I’d graduated from college with a degree in broadcast news. I resolved that if I didn’t get a job by January 1, I was going to join the Peace Corps; I’d saved several brochures and had begun to form vivid mental pictures of a thatched hut and a difficult but satisfying life in some torpid South American jungle.

But on Christmas Eve, I received a call in the cashier’s booth at work from a TV news director in Alaska. The station in Juneau needed a news anchor/reporter immediately, and the job was mine if I could fly there in two days. I asked for a week. I hung up the phone and stared into space, stunned at this unexpected resolution to my problems. My picture of a thatched hut in the jungle morphed into a metal Quonset hut in the frozen arctic.

A coworker asked, “Cara, are you okay?”

“Yes . . . Do you know if they have some kind of atlas around here?”

“What’re you looking for?”

“Juneau, Alaska.”

When I flew to Alaska, on New Year’s Day 1990, I didn’t think of it as running away. But running is a secret I’ve discovered hidden inside. It’s a secret I share with thousands of Alaskans who’ve moved here from elsewhere, who, whenever someone asks, “What brought you to the Last Frontier?” answer, “Adventure.”

In a land of runaways, adventure is both escape and salvation. The questions follow you here: buried in the hot heart of a glacier, riding the stubborn bore tide up Turnagain Arm, or perched atop the elusive peak of Denali. The answers are here, too: in the inquisitive eyes of a stalking black bear, the circling arms of a dip-netter calling a salmon to his death dance, or the soft pad-pad-pad of a sled dog’s feet on the snow of the Iditarod Trail. Running away solves everything. It has to, because when you stand at Point Barrow, at the top of the world, and see the arctic ice stretching before you for thousands of miles, you realize there’s nowhere else to run.

Yet ever since I got here, I’ve been trying to get back out—for nearly nine years. I once met a woman of forty who’d lived here for fifteen years. “I have an Alaska escape plan,” she said, “but I never seem to get around to it.” Like her, I both love and hate Alaska with equal passion.

In the years I’ve spent plotting my next escape, I’ve discovered the power of darkness, the purity of cold, and the secret of love. I’ve never lived in an igloo, but I’ve slept in a snow cave. The man who showed me how to build it taught me that a blizzard with wind-chills to ninety below zero is not very brutal at all, that nothing is as brutal as what we put ourselves through to hold onto love.

Imagine for a moment what it would be like to run as far as possible from all you know, to a land north of reality, a fantasy of emerald green and icy white, a place where pioneers still live. Imagine that when the arctic air has sapped your soul of all possible warmth, you will find a love that appears to give light and heat in a frozen world, only to discover that the love you’ve found is an illusion. Imagine that after you’ve lost everything, you can finally hear the heartbeat of the land. And, if you’re lucky, you will rediscover your own heartbeat.

But first, you must imagine that you are brave enough to run away.

thirty-five years old—anchorage to palmer, alaska

After nine years in the Last Frontier, I’m running away again.

My name is Cara Lee, and this journal is the record of two journeys: today, I began the first leg of a trip around the world, alone; today, I also began the first leg of a trip into the world within me, the tiny world inside my skull, which is still filled with the boundlessness of Alaska. It has taken me until this moment, as I leave the Last Frontier, to summon the guts, the hindsight, and perhaps most importantly, the time alone, to reflect on my life here. As I hit the road out of the state, I can finally, clearly see the path I rode in. For me, these two journeys have become one: I couldn’t dare to travel the earth alone if I hadn’t come to Alaska, and I couldn’t see Alaska plainly if I didn’t get some distance.

First, let me tell you about leaving Anchorage today, and give me a moment to steel myself before I tell you about arriving in Juneau nine years ago. I promise I’ll reveal everything, in time. I’ve never been one to hold back, even when it might have served me better.

You probably think I have good reasons for leaving. Don’t be too sure. I’m not. I can only tell you that somewhere along the way, amid all my running, I seem to have misplaced my life. Thirty-five arrived much faster than I expected. I once thought that by this time I’d have a husband, one or two kids, and a house, or at the very least, a dog—maybe a golden retriever. Instead, I have an apartment with a no-pets policy and my last boyfriend just left town. I once planned that by this time I’d land a six-figure contract as a TV news anchor in a major market. Instead, I’m a small market reporter with a six-inch stack of rejection letters. I once hoped to save the world, or at least a friend. So far, I haven’t so much as saved myself. Hell, I haven’t even lost those last five pounds. It’s not the life I once imagined. But with no attachments and no mortgage, I have nothing to lose. I’m free.

The idea of escape has often comforted me through trying times, but deciding to actually skip town feels like admitting defeat. Although I spent my childhood in L.A., I grew up in Alaska, the first place that ever felt like home. But even in this homelike place, I have yet to find the love and peace I yearn for. So now that I’m grown up, I’ve decided to hea

d out for one more search.

My itinerary is pretty sketchy. To start, I’m taking my car on a slow crawl south from Anchorage to L.A.—the place where I first packed my little blue suitcase—to see the family I left behind. After that, I’ll fly overseas for six months. Where? I’ve yet to decide. I plan to travel light, at least to the eyes of a casual observer; my stuffed lion is long gone, and my angst is too bulky to fit into a backpack.

The heroes of ancient Greek mythology underwent tests of strength, courage, and character to prove their worth. Each was typically on a noble quest to rescue others. I’m only trying to save myself. This may sound ignoble, but it’s the torch of modern psychology, isn’t it? The idea that one cannot help anyone else until he or she has first brought home the Golden Fleece of self-actualization. So, either I’m embarking on the next phase of a noble quest, or the most self-involved ego-trip ever.

***

I’d planned to leave Anchorage this morning. But, reluctant to spend hours trapped in a car with only my thoughts for company, I lingered with the evening sun and my friend Kaitlin.

Kaitlin and I are near opposites. We look different. I’m a short woman with short dark hair, large dark eyes, and a vaguely multi-ethnic look that usually raises questions—the short answer is Mexican, Chinese, Irish, English, Swiss, French, and Cherokee. “Cute” is the adjective I hear most often. Kaitlin is seven years older, but a head-turner with long blond hair, wide-set green eyes, and an unselfconscious giggle that could set a man’s pants on fire. We like different things. I like skiing, hiking, and camping; Kaitlin doesn’t like the feeling of cold wind on her ears, being sweaty, or sleeping outdoors. I’ve romanticized my career as a journalist into a crusade for truth and justice; Kaitlin enjoys selling real estate, because, she gushes, “It’s like taking someone on a shopping trip to Nordy’s, only better.”

They Only Eat Their Husbands

They Only Eat Their Husbands