- Home

- Cara Lopez Lee

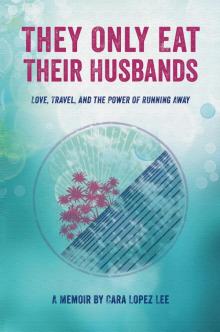

They Only Eat Their Husbands Page 10

They Only Eat Their Husbands Read online

Page 10

Having been taught that it’s safer to drive directly into a wave, I angled into the wind as much as possible while still making a course for shore. Having been taught nothing, Autumn was too frightened to push into the waves and, with a look of determination, she began paddling in the direction of least resistance . . . toward the vast open waters of Cook Inlet. The open water terrified me even more than the waves, so I continued toward shore. This soon created a gap between the group and me, as everyone else followed Autumn.

Chance paddled over to me. “Cara, we need to stay with the group.”

“Chance, she’s taking us out to sea. Besides, if I go that way, the waves are going to knock the side of my boat. We’re supposed to go into the waves. It’s not safe going that way.”

“I know, I know. You’re right, and I tried to tell her. But she’s scared and she’s not doing it, and it’s even more unsafe if we get separated.”

He was right. So, though it increased my terror, I turned to follow Autumn and Mike. As I’d predicted, the waves pummeled my boat, sending it lurching sideways. Also as I’d predicted, my boat rolled at a more alarming angle than anyone else’s, because my load was heavier on the side most vulnerable to the persistent waves. Pissed at Mike for shoving his gear so haphazardly into my kayak, and more pissed at myself for not rearranging my load just because he’d called me “anal,” I found it easier to deal with the situation. Anger was easier to deal with than fear.

In his gentlest, most persuasive voice, Chance coaxed Autumn to turn into the waves. I began to breathe again, as the open water that yawned before us shifted to my periphery.

When we reached the opposite shore, we paddled along the shoreline until we arrived at the mouth of Tutka Bay, where the air was calmer and the waves gentler. We passed small islands and rolling hills backed by powerful mountains, until we entered the passage to Tutka Bay Lagoon. The slender channel grew narrower and shallower until the water was just inches deep and my kayak scraped rocks on the bottom.

Just as I began wondering if we’d have to get out and drag the kayaks, we spilled out into the lagoon, where a small purse seiner was circling its net around a huge catch of pink salmon. We paddled into the midst of so many leaping salmon that there was never a moment when there wasn’t one in the air. The sight made me laugh with childlike delight.

We set up camp on the shore. Then Autumn and Chance went fishing, while I explored the tidal pools for sea stars and Mike took a nap.

In the evening, Chance and I paddled into the darkened lagoon and floated there while salmon cavorted and splashed around us. The distant murmur of Autumn and Mike’s voices was the only other sound. A fish leapt over the bow of my boat. “Whoa!” Chance said. “I hope one of them lands right in my kayak!”

After a brief silence he said, “I was proud of you today. You were so brave during that crossing. You were the calmest, quietest one in the group.”

“That’s because I was terrified.”

“Really? It didn’t show.” He dropped his voice, “You know, I was scared, too.”

“I’m glad I didn’t know that, or I would have been more afraid.”

“I was kind of pissed off at Autumn, too,” he said. “That was dangerous.”

“Really? I thought you were pissed at me.”

“No. You were the only one doing the right thing. It’s just that I knew we had to stay together.”

We stopped talking for a long time and just listened to the fish leaping around us. Then he reached through the moonlight, took my hand to pull our kayaks together, and kissed me—the weightless, lingering kiss of falling in love. “This is way special, babe,” he said. His blue eyes shone dark and liquid as the lagoon. The moon glistened on the water and in the scales of the salmon as they rose into the night.

***

The enchantment of that perfect night spilled over into the morning as we finished our tour down the long finger of Tutka Bay. Then we turned back to paddle for Hesketh Island, where we’d started two days before.

Along the way, we stopped at a wooden float and climbed out of our kayaks for lunch.

I pointed at the float and said, “Look at all those barnacles.”

“I think those are mussels,” Mike said.

“I’ve always wondered how you get mussels,” Autumn said.

“You go to the gym,” Mike said.

We all burst into laughter.

It was the last moment we truly shared. As we paddled on, we each drifted in our own little worlds. Mike and I pushed ahead. I looked back and saw that Chance and Autumn had pulled up side by side and stopped for a moment. He had his arm on her shoulder and they were leaning their heads together to share a private conversation. I turned away and paddled harder.

It took longer than we expected to reach the mouth of Tutka Bay. By the time we started the crossing to Hesketh Island, the sun was setting and a breeze was rising. At first it didn’t seem so bad, but soon we found ourselves in windier, wilder conditions than we’d encountered on our first crossing—and this time dusk was closing in. By the time we recognized our danger we were already at the halfway mark. There was nothing for it but to press on.

The evening grew darker. The waves attacked more viciously, tossing freezing cold water at me until my face was so wet I decided it was safe to let the tears fall without fear of anyone noticing. We barely spoke. Reaching the far shore seemed in doubt. The danger was real. It was too dark, and the waves were not only taller—maybe up to three feet—but also steeper and choppier than before. My kayak was taking a bitch-slapping, and so was my nerve.

To regain a sense of control, I began cussing at the waves, calling them names as I beat them with my paddle: “You cocksuckers! Fuck you! You’re not going to beat me, son-of-a-bitch! Fuckers! Fuck you, shitty little fucking waves! Take that! And that!”

Then, to distract my thoughts, I began the deep breathing I’d learned in aikido, breathing in rhythm to my paddle strokes: “In . . . out . . . in . . . out.” Sensei Sean had always gotten after me to “breeeeath” and “stand up straight.” I noticed I was hunching my back, so I sat up straighter.

The twilight deepened. The shore seemed as far as ever. I muttered the Lord’s Prayer.

When we reached shore, wet, shivering, and triumphant, I thought, Now I know I can handle anything. As we unloaded our kayaks, I told Autumn I’d prayed during the crossing, fearful of what might happen. “That’s funny. I never worry about stuff like that,” she said. “I always know God will take care of me.” The remark stung, as if she said my faith were inferior.

I brushed the subject aside and we started a fire and set up camp. I shivered through dinner, then went straight to my tent and fell asleep.

If only I could have slept through everything that followed.

***

In the middle of the night, I woke to the sound of two male voices pitched with so much tension it made my heart race. Mike and Chance were talking with a pretense toward calm that was more unbearable than straightforward yelling. It took me a moment to register what the conversation was about.

“It wasn’t supposed to be like this. I never meant it to be like this,” I heard Chance say in a choked voice. He spoke as if he’d caused an accident but had no idea how it had happened.

Then I heard Mike: “I told her I didn’t like you guys spending so much time together. ‘We’re just friends,’ she kept saying, and I trusted her. I should’ve known. You guys always sat too close together and leaned too close together when you talked.”

“I wouldn’t blame you if you wanted to hit me.”

“I’m not going to hit you. That won’t solve anything. I just want you to understand what you’ve done, how wrong it was.”

It’s funny how denial only seems obvious when other people are living in it. As I listened, the reality I’d been denying sank in: although Mike and I

had thought there were only two couples on this kayak excursion, there were three. The pounding waves of our crossing seemed inconsequential now, compared to the pounding in my chest.

Later, Chance came into the tent to find me wide-awake. “Did you hear?” he asked.

“I heard enough.”

He said nothing, just crawled into his sleeping bag. I remained silent for about an hour, until my chest burst open with a great heaving sob, then another, and another.

“Cara, be quiet! Cara, stop it! They’ll hear you!”

“You’re actually pissed at me?!”

“You’re making a scene.”

“Whose fault is that?”

“Try to think about somebody besides yourself,” he said. “They’ll hear you.” It was as if he still believed he could save their marriage, by sparing them my tears.

The next morning we all crawled silently out of our tents and retreated in pairs to different parts of the small beach—Chance and I in one spot, Autumn and Mike in another—but always in sight of each other because there was nowhere to get away. The water taxi was scheduled to pick us up at two in the afternoon. That was several hours away.

After a couple of hours, Mike suggested we all needed to talk. For the first time in my life, talking was the last thing I wanted to do. But I was too numb to object. We sat on a couple of logs and twiddled our eyes for a moment.

Mike’s voice was so quiet. “I’ve had a long talk with Autumn, and I told her I’d take her back. But she says she’s in love with you, Chance. She says she wants to be with you.”

“That’s not what I said, Mike! You didn’t listen to me.”

“Well then, what did you say? Didn’t you say you wanted to be with Chance?”

“Don’t do this to me,” she said, her eyes filled with tears, her jaw clenched.

“That’s not going to happen,” Chance said. “Whether or not you stay together, we never planned on being a couple. We just made a mistake. Anyway, it’s over now. You guys can still work on your marriage. I don’t want your marriage to break up because of me.”

“You still don’t get it!” Mike said. “Over the years there are bonds created in a marriage, bonds of trust. You’ve broken those bonds. They can’t be repaired that easily—”

I cut him off. “I don’t think we should talk about this now, because I don’t even know everything you’re talking about and a lot of this is none of my business. Some of it’s just between you and Autumn, or you and Chance, or Chance and me. Anyway, I don’t think this is the time or place.” I was amazed at how calm I sounded.

As we retreated to our separate corners, Chance complimented me for handling everything with such calm maturity. I’d only made the calm, mature decision to bury my head in the sand. I was a dignified fool.

I pretended to myself that as soon as we got off this damned island I’d leave Chance, that I’d be my own hero, the woman who was no one’s victim. But in the twisted, habit-formed places of my mind I was already formulating my plan to hang onto him. I would forgive him, he would owe me for that, and his guilt would make him mine. How could he leave me now?

Since my initial outburst, I’d remained dry-eyed, believing that more tears would only increase my humiliation. Meanwhile, Autumn wouldn’t stop crying. I’d taken up a restless, directionless pacing, and as I walked past her she tentatively said, “Cara . . . ”

“Yes?”

“I’d like to talk to you sometime.”

“I’m sorry, but I don’t really want to. If you feel the need, you can write me a letter.”

I’d tried desperately to make her my friend, but standing in front of this swollen-eyed wife and mother, I realized I didn’t know her. What good would it do trying to understand each other now?

During the long wait, Chance and I decided to occupy ourselves by making a banana cream pie. We rummaged in our dry bags for pudding mix, bananas, and other ingredients. After we mixed the filling and poured it into the pre-made crust, we dug a trench in the sand and filled it with ocean water. We floated the pie in the cold water to firm up the filling, and sat together silently watching it drift back and forth. When the pie was ready, Chance asked Mike and Autumn if they wanted any. They weren’t hungry.

As I absently pushed bits of pie into my mouth, I started to smile. I realized I’d suffered the pain I most feared and it hadn’t ended me. “I can’t believe you’re still smiling,” Chance said, and put his arms around me. He rocked me, and with each gentle sway I hated him, then loved him, then hated him, then loved him, as we looked out at the bay.

Time burrowed into the sand and disappeared like a crab, the air thick with the smell of salt water and lies, the silence broken only by the muffled sounds of the surf reluctantly lapping the shore.

Hours later, riding back to Homer in the water taxi, Autumn tried to cover the awkwardness with a joke, “Hey, Mike, how do you get mussels?” We all just looked at her. She cast her eyes down at the boat deck. No one spoke again.

Coming Home

Thirty-five years old—Los Angeles, California

Today a small package from Sean arrived in the mail. He sent me two books: Steve Martin’s Pure Drivel and a book of poetry by Billy Collins. Inside the flyleaf of the Collins book, Sean had written a poem of his own:

I miss you.

When the wind gently caresses the leaves into a song,

I dream of you.

He always gives the perfect gift: some little something that tells me he knows who I am, but something that also reminds me of him. I called to thank him.

“I’ve been thinking,” he said. “I’m so sorry for all I’ve put you through. I do love you, Cara. The only reason I’ve never committed to you is because I’ve been afraid of fucking it up.” He asked for another chance. He asked if he could come to L.A. to spend Christmas with me.

“I don’t know. I think we should move on. After Christmas, I’m going to be traveling a long time. We’re not a couple anymore.”

“You’re right. This is my own fault.” He started to cry. I’ve heard him cry before, though not often. It always makes my heart hurt, as if whatever’s happening to him is happening to me.

“It’s not all your fault. I’m not sure I could have made the commitment either. I’ve always blamed men for never making a commitment, but maybe it’s been me all along. By clinging to men who couldn’t commit, I’ve always escaped that decision.” I paused. “Look, this doesn’t mean I don’t love you, Sean. I’ll always love you, and I’ll always be your friend. My soul is connected with yours and it always will be.”

“I know. But it’ll never be the same, and you know it.”

“No, it won’t. But even if we ended up together, it would never be the same. Something always happens that no one expects. Nothing is ever the same. No matter what we do.”

His offer is tempting. But I’m not ready to trust him. It’s easier to think about trusting someone new, a man who hasn’t yet let me down. I haven’t given up hope on the man I have yet to meet, only on the ones I already know.

***

My jaw hurts. I’ve been clenching it at night again. This time the problem isn’t Chance. It’s not Sean either. It’s another man.

The last time I lived in a house with my father, I was nine. It was no fun the first time, tiptoeing around the icy draft Dr. Lopez left in his disciplined wake. Yet here I am, by choice, nine all over again. This time he is making an effort, which is almost more annoying. It was less complicated when he took no interest in me and I felt free to simply hate him.

Today he took me to the USC-UCLA game at Pasadena’s Rose Bowl Stadium. My dad now teaches public administration at USC and he’s a big SC fan. I’m not big on football, but I couldn’t turn down a chance at the father-daughter moment I used to dream about.

About a mile from the stadium we were bogged down in game-

day traffic, amid a flotilla of flatbeds and convertibles full of fans dressed in cardinal-and-gold or blue-and-gold, waving signs and ululating good-natured battle cries. My father is not a patient man. After his car crawled only one block in five minutes, he decided to park in a nearby neighborhood, saying, “We can walk the rest of the way faster than we can drive it.”

He certainly could. When I was a child I used to have to run to keep up with his brisk walk. “Hurry up, Cara!” he would say, rarely glancing back to see if I kept up, so that I always feared he’d lose me and never notice. Today, I did a sort of skip-jog. If I walked I’d lose him, if I ran I’d pull too far ahead. As usual he looked straight ahead, as if I weren’t there, as we zigzagged between other pedestrians.

Then my father zigged when I zagged. I stepped on his heel and went down, slamming into the sidewalk as if I’d been tackled. My loud grunt of pain was accompanied by a chorus of “OHHH!” from some two-dozen college kids crammed into the vehicles idling on the street. If it hadn’t been for their empathetic groans, I’m not sure my dad would have noticed.

He turned and said, “Oh my goodness!” (He’s the only man I know who can say “Oh my goodness!” without sounding effeminate.) Then, echoing several nearby voices, he asked, “Are you okay?”

The fall had ripped open my leggings and torn a bloody hunk of flesh from my knee, but I said, “Yeah, I’m okay.”

He apologized, and when we resumed walking he slowed his pace, although I still had to limp-hop to keep up with him. Several times in the ensuing half-mile, we caught each other’s eyes and chuckled. He mimicked my lurching limp and gurgled, “Walk this way!” like Igor from Young Frankenstein, and our chuckles turned to giggles. When we reached the stadium, he went to the concession stand and got some ice for my knee.

During the game, he explained every nuance of the action, the strengths of each team, and the stats of the players without a trace of his usual condescension. Together, we rolled our eyes when SC fumbled for the umpteenth time, and laughed when mascot Tommy Trojan rode his white charger onto the field and the fan sitting next to us shouted, “Shoot the horse!” USC lost, but I didn’t care. My father and I had laughed together, and this time the joke wasn’t on me.

They Only Eat Their Husbands

They Only Eat Their Husbands