- Home

- Cara Lopez Lee

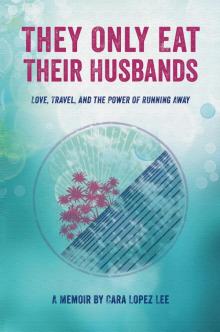

They Only Eat Their Husbands Page 9

They Only Eat Their Husbands Read online

Page 9

He wrapped his arms around me and kissed my forehead, “I left my baby doll alone all that time? I’m sorry.”

I was only partially mollified.

That night, Chance and I slept in the back of his Land Cruiser. In the middle of the night, we heard tapping on the window. It was Autumn. She’d only brought a warm-weather sleeping bag and she was cold. She asked if she could crawl into the SUV with us. “Sure,” Chance said. For the rest of the night, I only slept in angry little fits and starts, while Chance lay sandwiched between Autumn and me.

The next day, he invited her to hop into the inflatable boat with him again. The day was sunny and windy, and he’d hatched a plan to use his giant kite to pull them across the lake.

It was no small risk. This wasn’t one of those little paper or plastic kites I’d flown as a kid, but a broad nylon wing designed much like his paraglider. I’d seen him fly the huge red kite on land and watched it pull him off his feet many times. The powerful canopy could easily drag him into the water, or capsize the raft. People have died of hypothermia falling into glacier-fed lakes within swimming distance of shore, their pointless lifejackets firmly fastened about them. But crazy chances were the dots that connected Chance’s life, creating an alluring shape.

“We’re gonna make history!” he said.

“No guts, no glory!” Autumn said. She was brave, if not original.

I wanted to go, despite the danger. But no one invited me, and the boat could only hold two. Chance handed me a camera to record the moment. I was hurt, but too embarrassed to protest. Once again, I was a reporter watching from the sidelines, recording events in which I could not take part. In spite of myself, I was captivated by the beauty of the red kite as it dodged and dipped and painted figure eights in the sky. Propelled by a stiff wind, the kite dragged the boat through the water so fast that a large white wave spilled across the front of the tiny vessel, threatening to swamp it. My heart raced with the raft as I realized Chance and Autumn were about to die before my eyes. When they reached the halfway mark, I gave up standing watch and drove to the other shore to pick them up. I brought the boys with me. What would I say to them if we arrived to find two bodies floating in the lake?

But Chance and Autumn were standing at the water’s edge, wet and laughing. “Did you see that?” he said. “That was incredible!” Although they were giddy as kids, they were fish-eyed with a fear not yet shaken. As they dried off, Chance apologized to Autumn: “That was a pretty big risk. I should’ve let the kite go.”

Maybe if I’d gone instead of her, my different weight or different reactions would have dumped us overboard and killed us. But that thought didn’t help. I envied them this moment.

I never did get to try out that boat.

I did play with Chance and Autumn again, and again. I always felt as if they were the cool kids and I was the tagalong. The more this enraged me, the more I tried to fit in, and the more I tried to fit in, the more enraged I grew—until my emotions became a loaded gun, just waiting for someone to pull the trigger.

thirty-two years old

I had to leave Los Angeles and Denver behind and move to the Last Frontier to first notice the sounds of violence in the streets. I didn’t live in a bad neighborhood, yet the sound of gunshots at two a.m. became as unremarkable to me as the hum of a passing car. Anchorage cops told me that it was common at night for young people, often gang members, to drive around the city and shoot at each other, or just fire random shots for the hell of it, reveling in their power to dispense fear and death. I sat in Anchorage courtrooms and pondered the bewildered eyes of young men, boys really, who had shot and killed.

In spite of all that, life in Alaska taught me to appreciate guns. Maybe I picked it up by a sort of cultural osmosis; even if you subtract the gangs, Alaskan culture is, after all, a gun culture. That is to say, it’s still a frontier, with an “I’ll do what I damn well please and it’s none of your business” attitude.

It was Chance who first took me to a firing range and taught me to shoot a handgun. I felt an almost sexual rush of adrenaline. Maybe this is what people are so afraid of, I thought. Maybe something with the power to kill shouldn’t be so seductive.

A few months later that message hit home, the day Chance, Autumn, and I went to an outdoor firing range just outside town to shoot targets with his .45.

I’d made a concerted effort to become friends with Autumn. This was partly in self-defense—I thought if she learned to like me she would be less likely to cross the line with my guy—but it was also because I found her lively and likeable. Still, as my friendship with her grew, so did her friendship with Chance, and so did my jealousy.

That day at the firing range, Chance gave Autumn plenty of tutoring on how to fire his gun. He stood behind her, touching her arm, her shoulder, her waist, all ostensibly to help her learn proper body position.

Afterward, he and I returned to his condo alone. When I joined him in the basement to watch him clean his gun, I complained about his training session with Autumn. “You never help me that way.”

“You never seem to want advice. You always tell me to leave you alone.”

“Only because you’re so critical and treat me like I’m stupid when I don’t get something right away.”

“Okay, you’re probably right. Autumn even told me to go easy on her. She says I can talk kind of harshly when I’m giving advice. I’m sorry.”

Just then, I heard a noise in the house. “What’s that?” I whispered.

“What?”

“I heard something.”

We both fell silent, listening to our own breathing.

“Crap! I think we left the garage door open,” I said.

Then we both heard it, some kind of movement upstairs.

“Someone’s in the house,” I said.

Chance picked up the gun, loaded it, and pointed it toward the floor as he started creeping toward the stairway. Now all I heard was blood surging through my ears. I stood close behind him as he tiptoed up the stairs.

“Boo!” Autumn shouted, as she jumped down to the landing and found herself staring at the barrel of a gun.

“Shit!” Chance yelled, lowering his weapon.

For a moment we all stood transfixed.

Autumn broke the silence, “Oh my God. I’m sorry. That was really stupid. I’m so sorry. That was so stupid.” She walked back upstairs to leave, shaking her head and mumbling to herself.

Chance followed her outside.I sat down on the stairs and stared into space.

A few minutes later he returned. “She’s okay, just embarrassed,” he said. Then he started rambling, “We should never have left the garage door open. But she knew we were out firing guns today! She knew she never should have snuck in the house like that. She said she thought it would be funny. You realize we did absolutely the wrong thing? If there’s an intruder in the house, you’re never supposed to go looking for them. You’re supposed to wait for them to come to you.”

I just sat and stared.

“Jesus!” he went on. “We were just a split second away from a terrible tragedy. What would I have told her husband? Can you imagine? We almost turned her kids into orphans.”

“I need to go home,” I said, and stood up to leave. Chance gave me a hug, and I burst into tears.

“Yeah, that shook me up, too,” he said. “Are you okay? Oh God, I’m sorry.”

The following year, Chance signed up for an Alaska license to carry a concealed firearm. He often wore a suit or blazer, and—tucked into the back of his pants under his jacket—his .45, waiting for the day some madman might attack us on the streets of Anchorage. He admitted it was unlikely, but if it ever happened, wouldn’t I be grateful he wasn’t like the other “mindless sheep that go around unprotected, never thinking ahead?”

I didn’t fear madmen, gang members, or mindless sheep. I didn’t even fear Chan

ce, not yet. The only person I feared was Autumn, although I thanked God that Chance didn’t actually shoot her. I can’t imagine how we would have gone on from there.

***

It was months before I had the courage to confront Chance about my fears. He kept distracting me with his schizophrenic charm. He gave me a candy necklace made out of Sweet Tarts. He read me bedtime stories. One night we camped inside his condo: we put up a tent in the living room, built a fire in the fireplace, and slept in sleeping bags while listening to CDs of nature sounds like frogs, crickets, ocean waves, and rain.

But no distraction could make me overlook the disappearance of sex. And I couldn’t come up with enough baked goods, backrubs, or martyrdom to halt the primitive emotional ambush waiting inside me. One night, he sat soaking in the tub with lit candles around him and a beer in his hand. I knelt by the tub and asked if I could join him. He turned me down.

I picked at a loose cuticle with obsessive concentration and said, “We rarely make love anymore. Why is that?”

“I just haven’t felt like it lately. Do you want me to make love to you even if I’m not in the mood?”

“No. But you used to be in the mood a lot and now you’re not. I was wondering why.”

“Why do you think?”

“Maybe because I’ve gained weight?” I asked, thinking this was something I at least had some power to control.

“It’s not the size of a woman’s body that makes her attractive. You’re probably one of those annoying women who hurts other women’s feelings by always talking about how fat you are when you’re really not, aren’t you? Have you ever noticed that some fat women are very sexy, while some slim women with nice features are still unattractive because of their attitude?”

“So I’m not attractive to you anymore because of my personality? Is that the problem?”

“The problem is all these annoying discussions. You know how I hate this.”

I explained that the annoying discussions hadn’t started until after I’d noticed the distance between us. I told him I wanted to know what caused the distance in the first place. Looking back, it’s so clear now that all my double-talk was just a way of fooling myself.

Chance wasn’t fooled. “What’s this really about, Cara?”

“Okay. I’m worried because you spend so much time with Autumn.”

“Autumn’s a good friend.”

“Yes, but you’re both human, and I don’t think it’s healthy for you to spend so much time together when her husband and I aren’t around. It’s too much temptation.”

“You think Autumn and I are going to have an affair?”

“Yes. You might not plan on it, but . . .”

“Autumn would never do something like that. She’s a nice person.”

“I know she’s a nice person. Chance, nice people have affairs. Of course nice people would be attracted to each other. Who wants to have an affair with a jerk?”

“You shouldn’t worry about it. Look, I came in here to relax. Would you mind leaving me alone?”

He didn’t get out of the tub until the water grew chill gray, and he didn’t stop drinking beers until his face grew warm red. He passed out early in a deep, snoring stupor. If I was jealous of Autumn, I was even more jealous of alcohol because he spent more nights in its arms than in mine. I began to realize that was my real competition.

Lying next to him that night, I felt more alone than I ever did when I was alone. All my sexual frustration turned to boiling rage. I crawled over him, stood up, and yanked the covers off his body. When that only raised a mild grunt of annoyance, I tugged the pillow out from under his head.

“What the hell are you doing?” he grumbled.

I repeatedly kicked the futon, screaming, “Why are you doing this?! You fucking drunk! You’re ruining everything! I hate you! I hate you! I hate you!” Each time I screamed the word “hate” I punctuated it with a swift kick to the futon.

“Great. You hate me. I got it,” he said, his eyes narrow and flashing, like shards of broken glass. “Now can I sleep?”

Then I left.

I didn’t know which was worse, that those words came out of my mouth, or that I was never sure if he even remembered them the next day, when he asked me to come back.

***

The four of us stood at the back of the water taxi—Autumn and Mike, Chance and I—watching Chance’s yellow kayak bob through the water at the end of a towrope. It reminded me of a child’s toy boat floating in a bathtub.

We were all there to play a role in Chance’s newest heroic fantasy. “Autumn’s always telling me how she and Mike are having problems,” he said. “I think it’d be good for them to get out and do something fun together in the outdoors. And it’d be good for us to get to know another couple. Who knows? Maybe we can help save their marriage.”

I knew he meant it. Chance’s savior fantasy was fueled by a true desire to help, coupled with powerful self-delusion. He saved lives as a paramedic; perhaps he could resuscitate a drowning relationship. I wondered, too, if he was trying to rescue our relationship from the temptation Autumn presented. He was always trying to get the four of us together to do things. However, it was rare that both Autumn and her husband were available at the same time.

This time Chance’s plan was a four-day, three-night kayak excursion in Kachemak Bay. I’d kayaked only once before. So, to prepare for our trip, I took a kayaking seminar with Chance. Autumn and Mike had never kayaked before, but they couldn’t afford the seminar. In the unpredictable waters of Alaska, they’d be relying on Chance’s relative experience.

The water taxi took us to Hesketh Island, where we picked up three more kayaks. We were supposed to meet the taxi at this spot again in three days.

After we pitched our tents, we went for an afternoon paddle. In the glittering sunshine, Kachemak Bay flung a generous swath of multifaceted beauty. Snow-robed mountains rose above sparkling fjords that raveled away into unseen distances. Evergreens walked down nearly to the water’s edge, where translucent blue-green tidal pools hinted of glaciers tucked away among the folds of the fjords. We saw no whales or sea lions as I’d hoped, just a few otters, their wise and whiskered old gentlemen faces gazing at us with mild curiosity.

I relaxed into the uncomplicated labor of paddling as tiny waves nudged my kayak in a tranquil lullaby. The air was warm, but I never forgot that the frigid water could kill as fast as a weapon. If I fell in, I’d have only a few minutes to use my new skills to climb back into the kayak, or die of hypothermia. This knowledge added an undercurrent of tension to my reverie. With no real agenda, we set out for Elephant Rock, so-named for the obvious reason: the rock looked like the head, floppy ears, and dangling trunk of an elephant. Small waves surged through the narrow arch formed by the trunk, and we took turns surfing them in our kayaks. An electric thrill charged through me as each powerful little wave thrust me through the arch. Our laughter echoed through the rocky passage, then drifted away on the increasing wind.

Afterward, we paddled to a beach to take a break. “Where are the canned oysters?” I asked.

“Why?” Chance replied.

“Because I’m hungry.”

“Those are for later. We’re going to eat those as an appetizer with the crackers.”

“Okay, but I need to eat something. I’m really hungry.”

“Can’t you wait until dinner?”

“Damn it! I told you I wanted to buy some food of my own, but you insisted you and Autumn would buy everything. Remember I asked, ‘Do you promise I’ll be able to eat whenever I need to?’ And you said, ‘Yes.’ Now it’s only the first day and you’re already rationing me.”

“No, I’m not. I’m just telling you to wait.”

Autumn gave me a sympathetic look. “Chance, she’s hungry. Let her eat something.”

“I’m not giving her

a whole damned can of oysters.”

“I didn’t say it had to be oysters,” I said. “That’s just something I remember seeing.”

“Here, you can have my orange,” Autumn said softly, with a scolding glance at Chance.

“No, that’s okay. I’ll wait. It’s not like I’m going to starve to death. It just pisses me off. I hate begging. It’s humiliating.”

“I’m really not going to eat it,” she said, and thrust the orange into my hand.

“Thanks.” I accepted the fruit and, feeling deflated, sat on the beach to peel it. It was hard to swallow, each slice passing over a lump in my throat. So much for the ocean’s lullaby.

***

In the morning, we broke camp and prepared to make our way to another shore. I packed my kayak carefully, balancing the weight for stability in the water. I’d just finished when Mike walked up, peeked into the hull of my kayak, and said, “Great, you have room.” He then unceremoniously shoved something heavy into my kayak. It didn’t fit at first, so he pulled something else out, then wrestled everything back in.

“Wait! I’ve got it all balanced,” I said.

“I’m sorry, but I don’t have room in my kayak.”

“Okay, but let me put it in, so I can balance it with everything else.”

“Cara, don’t be so anal. You worry too much,” he said, and walked away.

After he said that, I felt too embarrassed to reach in and rearrange the gear. A few minutes later we shoved off.

We made our crossing into the teeth of a stiff wind, pushing into waves stronger and taller than any of us anticipated: maybe two feet high. Later, I’d stare at a ruler, calculating, and think, Okay, how is that a big deal? But a ruler is a single, stationary object, and it’s not rudely punching at my little kayak in angry bursts as I sway atop the dangerously chilly waters of Alaska. It might not have been so bad if the waves had been broad rollers we could ride up and down, rather than narrow chop that slammed into us over and again. I wondered if I was in over my head. I said nothing, but felt my eyes grow into the bulging state my friends call my “deer in the headlights” look.

They Only Eat Their Husbands

They Only Eat Their Husbands