- Home

- Cara Lopez Lee

They Only Eat Their Husbands Page 3

They Only Eat Their Husbands Read online

Page 3

A married couple living in Juneau once told me their small town was such a tough place for a single man to meet someone, that they knew guys who went to the airport to pick up women, “because they’d already dated every woman in town.” For me, it’s never been hard to meet men; if I stand still in one place long enough, an alcoholic is sure to find me.

Joe and I first met when a small group of journalists got together for lunch at a popular hippy-food restaurant called The Fiddlehead, named for the ferns that proliferate throughout the Tongass. Joe was a freelance journalist, but his rumpled clothing rode a fine wrinkle between aspiring poet and flat-out bum. He was obviously older than I, but how much older was hard to say. His long, dark, floppy bangs, bushy beard, and mustache obscured most of his face as effectively as a ski mask—as if he didn’t want to be noticed. In fact, what first caught my attention was how little he spoke. His mud-and-grass colored eyes clearly took in much, but gave away little. It would be weeks before I realized he was very opinionated, dismissing most people as either witless liberals, ignorant conservatives, or just plain idiots.

The few times he opened his mouth, he spoke in a gentle basso that almost fell below the range of hearing. As I leaned forward to catch his words the sound struck me as distractingly sexual, in odd contrast to his short, stocky frame. In the end, I blamed it all on the voice.

Joe lived on a sailboat in Juneau harbor, and on my first Fourth of July in Alaska, he invited a handful of reporters and photographers for a nighttime sail to watch the fireworks over Gastineau Channel. Until the Fourth of July cruise, it was always the stunning colors of fireworks that thrilled me most. But that night it was the sounds. The explosions bounced back and forth between the mountains of Douglas Island and Juneau with thunderous repeating echoes, as if the small pleasure boats bobbing around us were the ghosts of long-ago battleships. The strains of Jimi Hendrix playing his out-of-bounds rendition of “The Star Spangled Banner” floated to us from the shipboard radio. A pack of journalists ran around the deck like rowdy teens, waving sparklers that sizzled like bacon.

Joe, our captain, was the only one who remained silent throughout most of our brief cruise. Every shadow seemed to intersect in the place where he stood at the helm, so it was difficult to read his face. Later he confessed, “I had that party for you. Didn’t you know? I watched you all night,” so that now, in my memory, I see his curious eyes hidden in the shadows, following my every move.

At the time, I was unaware of his unspoken lust. How could I have known he even liked me? He barely spoke to me. As for my feelings toward him, he struck me as gnome-like in appearance and offbeat in manner, so that at first I had no more idea of lusting after him than a monk. However, I fell in love with the memory of that night.

After the fireworks, we all sang several ribald rounds of “Barnacle Bill the Sailor,” cracked tasteless jokes about Joe Hazelwood (captain of the ill-fated Exxon Valdez oil tanker), and poked fun at Alaska’s state lawmakers.

“Senator Fox told me his idea of the perfect way to spend the Fourth was sitting on his back porch with a six-pack and shooting off his gun,” Cheryl said.

We all laughed. But Joe, never one to let down his political guard, couldn’t leave it at that. “You should’ve mentioned that in your story last night.”

Cheryl gave him a puzzled frown. “It didn’t have anything to do with habitat protection.”

“You don’t think people would be interested to know that one of the lawmakers making decisions on their environmental policies is a gun-toting redneck who doesn’t even care about local ordinances against discharging firearms in a residential area?”

“Not unless there’s a salmon stream nearby,” Cheryl said. “Okay, it might have made a great bit of character nuance, but I only get two minutes to tell a story. Which part would you suggest I leave out?”

“That’s the problem with TV news, I guess: no time for the whole story.” He looked around him at several pairs of staring eyes and fell silent, although I noticed him studying me under his lashes, as if gauging my reaction.

When the party broke up, he stood on the dock and gave me a hand out of his boat. It was the only private moment we shared all night. As I jumped from deck to dock, my hand in his, this time he made no attempt to disguise his intense stare, which threw me off balance.

A few days later, when he asked me to go with him on a hike to Ebner Falls, I was lured by the remembered image of him leaping back onto his boat like an affable pirate. If I considered that he might be hiding a hook, it only intrigued me more.

***

The pirate set his hook with his element of choice: water. Joe couldn’t have found a better way to catch me than with a hike to a cascade. Water has always called out to that ancestral part of me that was born ages ago in its deep, wet womb. But Ebner Falls was the first glacier-fed Alaskan water to ever astonish me. Its color was the natural effect of glacial silt, but it called to my mind the unreal blue-green of an over-chlorinated swimming pool, roaring with a pure white froth.

The falls were just part of the scenery Joe and I passed as we hiked the Perseverance Trail. The trail was layered in twenty impossible shades of green: stilt-walking old growth spruce, hemlock, cedar, giant skunk cabbages, and curling fiddlehead ferns. Clouds draped themselves low and languid on the mountainsides, as if laden with secrets.

“Well,” Joe sighed, “this is pretty much what it looks like at any given point in the Tongass.”

“Yeah, all these miles and miles of natural beauty must seem really redundant after a while,” I retorted.

As we moved up the trail, past rusted equipment from the old Perseverance Gold Mine, Joe talked to me in the way of most news hounds, drilling me with questions as if he were interviewing me for a story. He seemed quietly impressed by all I said, while I was captivated by his attention. He apologized for his previous impertinent remarks about TV news, saying he thought the amount of work I produced in one day was phenomenal. “I’m amazed you can cover so many stories and still manage to eke out any information that makes sense.”

The more we walked, the more Joe found his voice, wedging bits and pieces of himself into the few openings I gave him in the mostly me-sided conversation. He told me he was the youngest of three children and the black sheep of his family. “My sister thinks I should get married. My brother thinks journalism is just a hobby and I should find a more respectable profession. I think they’re just worried someday I’ll show up penniless on their doorstep and embarrass them in front of the neighbors.”

“I’m the black sheep of my family, too,” I said, “which is a neat trick, since I’m an only child. My dad thinks I’ll never amount to anything with just a bachelor’s degree, my grandmother thinks I’ll never get married because I hate to cook, and my stepmother just thinks I’m a lousy daughter.”

“Why?”

“I borrowed two thousand bucks from my dad to ship my car and some of my other stuff to Alaska—the TV station wouldn’t pay moving expenses. Anyway, I didn’t realize how high the cost of living was up here, so I’ve only been able to pay back a few hundred bucks so far. So my stepmom thinks I’m a flake.”

“I disagree. I think it takes a lot of character to come this far away from everything you know and start a new life.”

“Or it takes a real flake.”

He paused, then said, “They say everyone who comes to Alaska has a dream. So, what kind of dreams do flakes have?”

“I want to work as a reporter in Alaska for a year or two, then work my way up to a top-twenty market in the Lower 48.”

“So, you’re another one of those people who just came here to grab the oil money and run?”

To a non-Alaskan his accusation might not make sense, but Alaska’s economy is driven by oil, and everyone who lives here benefits from it, directly or indirectly. Plus, Alaskans don’t pay state taxes. Instead the state pays t

hem; every resident is entitled to dividends from the state Permanent Fund, an investment account created with oil royalties. After a year, I was eligible for my first check. During my time in Alaska, the size of my annual dividend check has surpassed the thousand-dollar mark.

But I refused to be labeled a mercenary. “That’s not it at all. I came here because it was the only place I could get a job. And I’ll have to leave if I want to advance my career.”

“A dedicated journalist doesn’t do it for money.”

“You mean we’re the fourth arm of government, defenders of truth, freedom, and democracy? I believe in all that, too. That’s why someday I’d like to have the resources to do more in-depth stories, and that’ll never happen at a small-town TV station.”

“I understand. I guess I’m just being selfish. I was hoping you’d stay.”

“So, what about you?” I asked. “What kind of dreams do black sheep have?”

“I want to take my boat sailing around the world. And I’d like to visit Ukraine. That’s where my ancestors are from.” He went on, “I did a story once in the Russian Far East, and one night I sat around a campfire with a bunch of locals. It was freezing, but they passed around a bottle of vodka and told stories and laughed all night, while I sat there shivering. Anyway it got me thinking, someday I’d like to visit my grandfather’s village and pass a bottle around a fire.” He smiled disarmingly. His smile wasn’t remarkable of itself, except for its bright contrast to his otherwise intensely serious demeanor. By that measure, it was a knockout.

After our hike we went to the Red Dog Saloon, where I drank a beer and stapled my business card to a wall plastered with them, while Joe practiced his vodka-drinking and storytelling skills on me and anyone else within earshot. They weren’t “stories” so much as loud, rambling pontifications on nothing in particular—although at one point I think he said something about fighting to hang onto “the Alaskan way of life.” Customers gave him irritated looks. I shushed him, and he loudly insisted I not shush him.

When we left, he walked me to his office near the docks. It was a transparent move to impress me with his dashing profession. The office looked like that of an absent-minded professor, mismatched second-hand furniture barely visible beneath stacks of magazines, newspapers, and photographs stained with coffee rings.

I sat in a swivel chair and turned slowly to take in the black-and-white photos that peppered-and-salted the walls. There was an Alaska Native girl, Tlingit I think, cutting fish with an ulu: a curving, fan-shaped blade set into a bone handle. There was a weathered-looking commercial fisherman standing below a haul of halibut hanging from a winch: each huge and hideous fish had a pair of bulging eyes on one side of its head, which seemed to stare accusingly at its killer. But the photo that struck me most was of a pair of trumpeter swans flying over a sparkling wetland: lovers in flight captured by the lens of a loner.

As I stilled the office chair to gaze at the swans, Joe stepped behind me and massaged my shoulders, his hands so fast and clumsy that, instead of relaxing me, it agitated me. I stood abruptly and turned around, hoping he’d stop. Mistaking this signal, he kissed me, gobbling at my mouth like a cannibal. His mouth tasted of stale booze, and the room closed in as I tried not to gag. Insidiously, it was at that moment more than any other that I was hooked, lured by the potential to explore this man’s inner depths. He must have them; why else would a creative and intelligent man drink?

Two weeks later, we spent the night on his boat in the harbor, talking and making love until dawn to the hiss and glow of an oil lantern, the murmur of Joe’s baritone whisper, and the sensual sway of the sea.

Before I drifted off to sleep, I finally got the courage to ask his age. He was thirty-eight, eleven years older than I. “Is that a problem?” he asked. “Of course not,” I said. I still felt like a child and I hoped hanging around with a grownup might rub off, though I didn’t say so.

Cheryl later told me, “Be careful, Cara. He’s got quite a reputation.”

“You mean with the ladies?” I asked with genuine surprise.

“No, as a drunk.”

“He doesn’t drink that much. And he’s a lot different than I thought he’d be. Once you get him talking he’s really interesting, smarter than anyone I’ve ever dated before. He can be sweet, too, and very romantic.”

“That makes sense. He is a journalist. Creative people can be very romantic. I’m sure he’s very exciting. Just . . . be careful.”

But the warning itself, “Be careful,” only added to the attraction. That’s what someone always tells you just before the fun begins.

***

The allure of a glacier is that it’s not merely beautiful, but also overwhelming and potentially dangerous. A glacier is best understood if you stand silently and listen to its creaking, groaning heart. Its beauty is the result of intense pressure. A glacier forms when the weight of tons of snow forces the snow beneath it to compress into ice. The pressure is so extreme it heats up the molecules and melts them into liquid in the instant before they form ice. That is why a glacier flows: however cold and forbidding it may appear, there is a place inside that burns.

It was Joe who took me to see my first Alaskan glacier up-close. Juneau’s Mendenhall Glacier undulated toward the lake like an icy tidal wave, thrusting its way through the surrounding mountains, carving valleys in its powerful wake. I stared in neophyte awe at the wall of deep blue-upon-white, tortured and lovely, monstrous in size, frightening to consider, with man-eating crevasses lurking across its expanse.

Joe told me he’d once hiked across a glacier and fallen into a crevasse. “That may have been the scariest moment of my entire life. I had no idea how far I was going to fall. Some of those crevasses can go down more than a hundred feet.” He didn’t fall that far. A fellow hiker pulled him out.

He handed me his camera and taught me how to take better photos. He stood at my shoulder, and his soft-spoken words tickled my ear, “If you want less camera shake, take a deep breath . . . then, as you press the shutter, exhale slowly.” Ironic, that this advice came from a man who I remember most vividly from the moments when he was unsteady and swaying.

He was not gentle and quiet then.

Those were the times when he attacked my professional worth: “Why don’t you become a real journalist instead of a TV reporter? Are you afraid of coming up with sentences that have more than three words? Afraid to expose how little you really understand?”

Sometimes his comments didn’t make sense, things like, “If I wazh a sailor I’d drink the ocean. But you wouldn’t unerstan’ ’cause you don’t know what it’s like to sail.”

“What are you talking about?”

“You know exackly what I’m talking aboud. Don’t pull that lunatic crap on me! You’re just like my fugging family.”

“Joe, have you been drinking?”

“What does that have to do with your ignorance?”

The next day a tormented Joe would whisper a tender apology, still sounding confused. I think he often didn’t remember what he was apologizing for.

Of course I thought about telling him to take a hike. But Joe was my guide to falling in love with the Last Frontier. He seduced me with his passion for Alaska.

One night as we lay awake on his boat, rocked by gentle waves, Joe said, “I love you, Cara.”

I was silent.

He turned my face to the moonlight to confirm the tears swimming in my eyes. “That’s supposed to make you happy. It’s not supposed to make you cry.”

I knew the usual response was supposed to be, “I love you, too,” but I wasn’t there yet. Still, I felt a mournful tenderness for this man who walked out of step with the rest of the world, so I came up with the oblique response, “Except for time, I’m already in love with you.” In the manner of a man in love, he did not question this inane line of crap.

I kn

ew that falling in love with Joe was likely to get me into trouble, and only partly because I was leaving to start a new job in the big city, which locals jokingly referred to as Los Anchorage.

***

At Thanksgiving, Joe flew to Anchorage for a visit. He arrived stumbling drunk. The moment he stepped off the plane he began bowing deeply to total strangers, waving his Russian-style fur hat with a flourish and loudly pretending to speak Russian. We went out to dinner, where I begged him to take off the hat and stop drinking.

“You need to pull your head out of your ass and have some fun,” he said.

In the morning he apologized again, kneeling beside my bed like a penitent child. His apology was vague, referring only to “last night” and his “behavior.” It was clear that, once again, he had no real recollection of what he’d done.

On Thanksgiving Day he drank a fifth of alcohol, whiskey I think. He was so drunk I refused to let him help me shop for the meal. I wouldn’t let him help me in the kitchen either.

“You’re treating me like a little kid,” he said.

“It’s just that I can’t concentrate if anyone else is in the kitchen,” I lied.

He wasn’t fooled, but he gave up and retreated to the living room to drink and sulk.

I’d invited my roommate Max and one of his friends to join us, and they soon came out of Max’s smoke-filled room to socialize. They seemed oblivious to the tension in the air, probably thanks to the generous appetizer of marijuana they’d inhaled.

At the time, possession of an ounce of marijuana for “personal use” was still legal under Alaska law, thanks to the state constitution’s strong stand on the right to privacy. There were still laws against buying and selling it, so how anyone was supposed to obtain this supposedly “legal” dope was a mystery.

During my first few months in Anchorage, Alaskans debated the ballot issue that would make marijuana possession illegal in the state. When the measure passed, I said goodbye to my roommate. He was a sweet guy, docile as a kitten, but I was a reporter with high ambitions, and I didn’t want to risk being linked to someone engaged in illegal activity, no matter how legal it had been a week before. Besides, his room was kind of scary, and the smell of dope was slowly permeating the entire apartment.

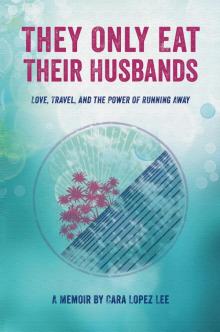

They Only Eat Their Husbands

They Only Eat Their Husbands