- Home

- Cara Lopez Lee

They Only Eat Their Husbands Page 4

They Only Eat Their Husbands Read online

Page 4

But on that Thanksgiving, I was grateful that Max, his friend, and their dope were all present to mellow out the rough edges of the drunk I’d invited to stay. By mealtime, I’d had a couple of glasses of wine myself in the spirit of assimilation and in the hope of picking up the strange rhythm of the sporadic conversation. Joe talked politics, which regularly reminded Max and his buddy of some sophomoric movie that had made them “fall on their asses laughing.”

The dinner turned out perfectly. The two men with the raging munchies showered me with compliments, until even Joe had to admit the turkey was delicious. Triptophan perpetuated everyone’s dull stupor late into the evening, and gave me the one thing I was most thankful for that Thanksgiving: the moment when Joe passed out.

The next day, Joe and I went cross-country skiing in Russian Jack Springs Park and stopped to watch several moose munch on birch bark just off the trail.

As we continued down the trail, he said, “If you have to live in Anchorage, I can see how this greenbelt would be a compensation. Too bad you can still hear the traffic, though.”

“You really do hate Anchorage, don’t you?”

“It’s just that it’s not really like living in Alaska. I mean, if you want to live in a city, why not go to Los Angeles?”

He was scheduled to stay for four days. He left after three. I barely stopped the car long enough to let him out at the airport and drove away without looking back.

If I’d known that moment at the airport was the end of our relationship, I might have come up with a scathing tongue-lashing, or at least burned rubber as I drove off. However, a few months later I was grateful I’d refrained from saying anything I might have regretted.

It was while ripping Associated Press wire copy in our newsroom that I first learned what happened to Joe. According to the AP, he was found unconscious and bleeding in an out-of-the-way corner outside a building in Juneau. Muggers had stabbed him in the neck and left him to die. He was drunk, which might be why they’d targeted him.

I called Cheryl. She told me what the AP didn’t say: that Joe was so drunk the surgeons were sure he would die because it was too risky to give him anesthesia for the surgery he needed. They feared the combination of alcohol and anesthetics might put him under forever. “They finally operated, and he came through it. But he’s still not out of the woods,” Cheryl said.

I wanted to cry, but instead launched into irate invective: “I’m sorry, but this whole thing really pisses me off at Joe. It was his own stupid fault. If he hadn’t been drinking they probably wouldn’t have attacked him. He might as well have slit his own throat.”

Cheryl warned me against that kind of talk. “That’s just a way of re-victimizing the victim. However drunk Joe was, the animals who stabbed him and left him to die were to blame, not him.”

When he regained consciousness, she called me back. “I went to visit him. He looked so terrible it was hard not to cry. You know, hardly anyone has gone to see him. A lot of people are talking like he deserved it. Even his family didn’t come. You should call him.”

So I did. His voice was as hoarse as a tonsillectomy patient’s, and he didn’t say much except to repeat how glad he was I called. I told him I was grateful he was okay. I refrained from telling him I was furious with him for almost getting himself killed. He’s the one who said it: “I know if I hadn’t been drinking this might not have happened. I know I have to change or I’m going to die. I know I’m killing myself.”

His words filled me with pity, but I resisted the urge to hop a plane to see him. It wasn’t that hard to resist. I knew Joe found pity annoying. I knew we’d ultimately find each other annoying. I knew our different visions of Alaska were taking us down different paths, and I was already gone.

***

To Alaskans like Joe, the only good thing about Anchorage was its location, “just twenty minutes from Alaska.” To me, the Anchorage Bowl looked like a 1970s strip mall in the midst of a resplendent castle: the city’s hasty architecture seemed out of place against the rugged turrets of the Chugach Mountains and the shining moat of Cook Inlet. Like other cities, Anchorage had tall office buildings and trailer parks, corporate lawsuits and gang warfare, indoor plumbing and cable TV. There was not a single MacDonald’s. There were ten.

But the rush-hour-gridlocked, car-exhaust-hazed exterior didn’t fool me for long. Somewhere within Alaska’s biggest city, thrumming beneath the heaving, pot-holed asphalt, there lay a deeply primitive place. Moose and bears still roamed among us, and sometimes they killed. Every winter, ice and snow tore the lines right off the road, frost cracked open the pavement, and people plugged in their cars to keep them from freezing.

Anchorage had no more snowfall than many cities in the Lower 48. The thing was, it never seemed to melt. For six months, plows pushed snow into towering berms that never shrank, but grew and multiplied in winter the way dandelions do in summer. I loved the mounting snow; in the darkness of winter, it reflected and amplified the meager light of the brief daytime sun and the electric lights of the long winter nights.

Of course, Anchorage wasn’t nearly as cold and forbidding as the Arctic, several hundred miles to the north, where the freezing air was usually too dry to snow. Anchorage wasn’t even as cold as some places in the Lower 48, thanks to the Japanese Current—I never fully understood how this Pacific Ocean phenomenon worked, just obediently repeated the phrase “Japanese Current” to anyone from “Outside” who asked me, “Isn’t it cold up there?”

It wasn’t the cold that I struggled to survive. It was the dark.

Someone once told me that living through an Alaskan winter was like turning the lights off for six months. For six months, we lost a few seconds to a few minutes of light each day until we reached the winter solstice and fewer than four hours of daylight. Then, for the next six months, we gained a few seconds to a few minutes of light each day until we reached the summer solstice and more than twenty hours of daylight.

“The summers make up for the winters,” Cheryl said. “You get all that sunlight back.” Certainly the long days of summer were energizing. In fact, by summer solstice, I felt manic. I remember going out with friends to Chilkoot Charlie’s, where the city’s middle class dressed down and its sleazy dregs dressed up to play bad pool, dance to cover bands, and drink away the few hours of darkness. The sun was barely beginning to set when we walked in after eleven p.m., and dawn was just teasing the sky when we left at three a.m. I often couldn’t sleep at night, for all the light sneaking into my room beneath the curtains. Some people put aluminum foil on their windows to block the light, but those homes always made me feel as if I were sitting inside a casserole dish.

So, no: for me the lost sleep of summer did little to make up for the long sleep of winter. Over the years, the effects of the darkness seemed cumulative, so that each winter felt more depressing than the one before. Like fungus, all my festering disappointments grew in the dark. I wasn’t alone. At the TV station, I reported one story after another in which Alaskans outpaced the national average in alcoholism, drug abuse, domestic violence, and suicide. Most suicides happened in spring, but only because killing oneself required more energy than anyone could muster in winter. I blamed it all on the clinging night. But, like other Outsiders who yearned to belong, I embraced my suffering as the hazing ritual required to make me a member of the club. Surviving the darkness was Alaska’s secret handshake.

At first I felt disappointed that the dramatic six months of total darkness promised to me by friends who’d never set foot in Alaska was not as they’d advertised. Then, as a reporter covering the rural Alaska beat, I flew north to Barrow, to do a story on the year’s last sunset, prelude to the longest night in the world.

Point Barrow is truly the northern edge of the earth. As the photographer and I stood on the shore staring at the junction of the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas, my brain refused to register that there was any

kind of sea before my eyes. All I saw was a white expanse of ice so vast it made me want to cackle like a madwoman. Strangely, I was reminded of an endless wheat field in Kansas, the only image I could think of that was remotely akin to this. The only things that prevented the frozen sea from appearing flat and monotonous were the random humps and ridges of shifting ice. I might take off across that ice, enter another dimension, meet God, continue walking for eternity, and never reach any destination; or I might walk for five minutes and end up back where I started—all without the least surprise.

At 12:35 in the afternoon on Sunday, November 18, we turned our eyes east to watch the last sunrise of the year. A tiny, distant ball of glowing embers shyly lifted itself to peek over the horizon, then swiftly crawled a few inches across that imaginary line. Tiny crystals of ice fog gave the air a sparkling, reflective quality. In the hour and twelve minutes from sunrise to sunset, the sun’s feeble rays turned the ice fog into rainbow dust shivering atop the arctic plain.

At 1:47, the sun disappeared off the edge of the earth. It would not rise again until January 23, more than two months later—not six months, as my friends “down in America” believed. Still, that was a helluva long night.

“It’s so eerie,” I muttered. “It’s like we’re standing at the end of everything.”

It was a powerful ending, the death of the sun at the end of the world. Although the sight moved me, the immensity of the pitch-black night that followed was almost disturbing. I never again romanticized the notion of living in darkness for six months. As it was, the semi-darkness of an Anchorage winter was enough to suffocate joy, and each succeeding plunge into the long winter night fed my ultimate desire to escape.

Alaska Escape Plan

thirty-five years old—haines, alaska to bellingham, washington

Last night, lying in a motel room in Haines, waiting to catch the ferry south to Bellingham, Washington, grief over my unleashed past and fears over my unplanned future pressed inexorably on my brain. My mind felt like a wad of over-chewed gum, and I had no energy left to keep chewing. I’ve discovered that only one thing can make me feel better when I get that wound up: talking to Sean, the last Alaskan man I tripped over. Until he left the state last month, Sean was alternately my lover and best friend.

He barely answered the phone before I began weeping uncontrollably. I said that I felt close to a nervous breakdown, that I wasn’t sure I could even make it to Seattle, that there was a chance someone would have to come scrape me off the floor. The perfect listener, he didn’t tell me everything would be all right. He simply allowed me to fall apart.

After I moved uninterrupted from hysteria to repetition to exhaustion, he said, “I wish I could be there with you. I wish I could help. I don’t know what to say.”

“That’s all I needed to hear. Just talking to you always makes me feel better.”

“Well, I didn’t do anything, but I’m glad you feel better. You know, sometimes I worry about you. Then I think about it and I realize you’ll always be okay, because you’re an amazing person, Cara. But if you ever need to talk, you can call anytime. I really miss you.”

When I hung up I felt stronger, just knowing that someone in the world missed me tonight and that he thought I was so amazing I could survive anything, even my darkest thoughts. My eyes swollen and my emotions drained, an uneasy post-storm calm settled over me and I fell into a restless sleep.

The Last Frontier

twenty-nine years old

I wonder how different my relationship with Sean might have been if I’d seen celibacy versus sex as two ways to express a relationship, rather than two ways to avoid one.

Six years ago, Kaitlin and I decided to take a martial arts class. I chose aikido, which roughly translates as “the art of peace.” This appealed to my aspiration to achieve enlightenment, which tended to surface between boyfriends. Still, I was impatient to kick ass and a little disappointed that, before we could learn to fight, we had to learn to fall.

My impatience soon vanished, when Sensei Sean was assigned to teach us how to roll. When Sean approached us on the mat, I didn’t know he was a third-degree black belt and a sensei. I only sensed his high rank because he was one of the few people wearing a hakima (a pair of intricately tied, loose black pants that looks like a skirt). I elbowed Kaitlin and rolled my eyes in our silent shorthand for the teenybopper shriek, “Oh my God, he’s sooo cute and he’s coming this way!” He had a stocky body, a strong chin, and tattered curls of brown hair. I had to make a conscious effort not to stare into his perpetually amused eyes, which were an impossible shade of blue—were those colored contacts?

“We teach you to roll first because we spend a lot of time being thrown on the mat. Safety is most important,” he said. He then demonstrated, flowing low across the mat like a sudden rush of water. I followed, slamming across the mat like a bag of rocks: elbow, shoulder, head, spine, ass . . . bang, bam, whap, ouch, oof. We rolled throughout the entire class, until I felt like a mass of bruises and my shoulder throbbed.

“I keep hurting my shoulder,” I told him.

“I see that. It looks painful.”

“Is there a better way to protect my shoulder?”

“Don’t leave it out there.”

“Thanks.”

Afterward, I told Kaitlin I thought he was handsome and funny.

“Yes, I noticed you asked for an unusual amount of instruction,” she said.

I went on as if I hadn’t heard her, “But I think he knows he’s cute. He seemed kind of arrogant.”

thirty years old

Over time, I discovered that Sean was far from arrogant. Off the mat, he was a shy, diffident man who preferred to listen and observe. I discovered something else: off the mat, he had a girlfriend. So, on the mat, I became just another admiring student.

Sean was an excellent teacher who conveyed a sense of wonder, as if he’d discovered each move just a moment ago. He spoke about “staying in the moment” and “letting go of the mind” in ways that made those ideas sound tangible. When he trained with the other high-ranking udansha he spun like a dervish and flung his small body through the air like an acrobat, his face full of a Puckish mischief that tickled the watching students into spontaneous laughter.

The time came for my first test. I was too naive to realize that a properly humble beginner would never have the audacity to ask a Ni Dan (third-degree black belt) to be her uke (the training partner who is continually thrown during a test). Too polite to point out my faux pas, Sean agreed to be my uke, telling me he felt “honored” that I’d asked.

He trained with me patiently, full of silliness and wisdom. “Do you see what’s happening here?” he asked as I tried to escape his grasp. “You’re pushing right back into my strength. We’ll be here all day. Now, if you work around it . . . See? You’re no longer fighting my strength, but working with it . . . Then, you can redirect it, and . . . stick your finger in my ear.”

The day of my exam, he brooked no nonsense. Shortly before the test, I was standing amid a crowd of practicing students, hands folded in front of me in a self-conscious Eve pose, when Sean appeared and his fist flew into my clasped hands. I flinched and grabbed my stinging knuckles, staring at him saucer-eyed. “Don’t ever stand like that,” he said. “You’ll get hurt. You should always stand in a ready stance. Relaxed, but ready. Work on your awareness.” I never stood like that again.

During the test, it felt like we were dancing in a graceful pas de deux, except for the sweating and grunting and the bodies slamming into the mat. I passed.

A few days after my aikido test, he came to my thirtieth birthday party, which I’d dubbed “A Funeral for my Youth.” Sean was one of the few who dressed in black, as per the party invitation, and I thanked him for remembering. “Don’t give me too much credit,” he said. “Black is my favorite color. I probably would’ve worn it anyway.”<

br />

I’d also asked the guests to submit advice for people over thirty. Sean’s contribution was a list of “new pick-up lines for over-thirties” such as, “Hi, I’m a martial artist and I’m here to help.” I’d asked everyone to skip gifts, but he brought one anyway: a traditional sake set. As he presented it, he said, “It’s not really a birthday gift. It’s a tradition for the uke to give the nage a gift after the test.” The way he smiled sideways made me realize that the tradition was quite the opposite; I should have been the one to give him a gift.

I allowed him to let me save face, with a dip of my head and a penitent smile. “Thank you, sensei. By the way, I realize now that I was overstepping my place by asking you to train with me. You must’ve thought I was a brazen little thing.”

“No, I thought you were pretty brave. Most people would’ve been afraid to ask. But you don’t seem to have any fear.”

“Oh, I’m afraid of everything. But I just ask myself, ‘What would I do if I wasn’t afraid?’ Then I do that.”

“Now that,” he said, “is living in the moment.”

He hadn’t brought his girlfriend to the party. They had a reputation for being on-again, off-again. But there was no point in wondering about their current status, because by then I’d started dating someone else. Tommy was at the party, too, but he spent most of the night hiding somewhere by the pony keg and said very little to me all night. Tommy wasn’t so much a boyfriend as a placeholder. But, at age thirty, I thought it important to entertain all options.

Sean used to say, “The life you live, you make all these choices, all these decisions. But in the end, it’s all about timing.”

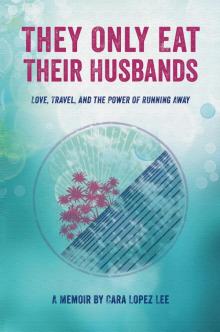

They Only Eat Their Husbands

They Only Eat Their Husbands