- Home

- Cara Lopez Lee

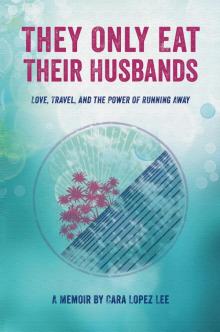

They Only Eat Their Husbands Page 7

They Only Eat Their Husbands Read online

Page 7

Pete suggested, “Take plenty of pictures. And write down what they are. I can’t tell you how many photos I have that are like, ‘well, this is a mountain somewhere.’”

Sam advised, “Don’t let your view of the world narrow down to the tiny square of your camera’s viewfinder. Stop taking photos sometimes and just look around.”

Pete said, “Be open to getting to know local people. Some of my best travel experiences have been with people who offered to show me around, or invited me to their homes.”

Sam said, “There are a lot of con artists out there, and people who’d love to take advantage of a woman traveling alone. Trust no one.”

Later, there was a stir of excitement among the passengers when twenty to thirty porpoises began leaping next to the boat. I called Sam over to take a look; Pete was nowhere in sight. Sam sauntered over and leaned against the rail in a James Dean slouch. As we watched the sleek gray bodies torpedo through the water, I thought I heard one give a squeaky call. Then I turned and stared suspiciously at Sam as he gazed seriously off into the distance. “Is that you?” I asked. He started laughing, and I elbowed him in the ribs.

Tonight, as we sailed south into clearing skies, the northern lights appeared. Almost everyone on the back deck was asleep, except Pete, who sat in a chair out in the open, staring up at the sky. “You know,” he said, “studies have shown that, when the northern lights appear on this side of the pole, there’s a mirror image on the other side.” We both fell silent as we watched the silky green and red cape cast itself trembling and crackling across the cold, dark sky.

Alaska is not just a place. It is an idea. For those who are cast adrift, it is a place to drop anchor. For those who wander, it is a place to call home. For those whose lives are defined by longing, it is a dream of desire fulfilled. If my soul had a name I would call it Alaska, the Last Frontier. I’ll be gone before winter puts Alaska to sleep again. But this place, this idea, will forever imbue my black-and-white dreams with shifting colors, as the angels that dance in the Aurora Borealis whisper, “You can leave us. You can leave it all. But we will never leave you.”

A good thing they won’t. It’s lonely traveling on my own, and a little company couldn’t hurt—real or imagined, friend or stranger.

Coming Home

thirty-five years old—los angeles, california

My contacts burned and phlegmy grit coated my throat as I was swallowed by the omnipresent brown cloud of Los Angeles. Home—as if this impersonal place that has chewed up and spit out so many dreamers could have nurtured anyone. I wasn’t eager to reach my father’s house, where I always forget who I am, instead becoming the person he and his wife think I am. But this time his wife would no longer be there. So who would I be?

While the idea of my own death has always left me alternately curious and petrified, the death of others only embarrasses me. I’ve heard that I need not weep for the dead because of the hope of heaven. Yet whenever someone dies, I fear that my inability to exhibit feelings of sorrow or pity will only raise suspicions I might be a sociopath. The death of others only puzzles me. A person was here; now he or she is not. How odd. The only emotional reaction I’ve ever been certain of in the face of death has been to realize my connection to those left behind.

Los Angeles began to lure me back several months ago. My father made the phone call telling me my stepmother had cancer, but I knew it was really the voice of the great smoggy beast gurgling, “Bring me more flesh on which to feed.”

Dad said I couldn’t tell her I knew because she’d made him promise not to tell anyone. It was a secret they’d kept for nine years. “But I don’t think that’s right,” he said. “I think family should know these things. Anyway, now the doctors say it’s touch-and-go, and I didn’t want you to be surprised if I called with bad news.”

He avoided the word “dying.” It seemed I wasn’t the only one who found death embarrassing. Maturity might make us comfortable being caught in any number of unintentional crudities: flatulence, stray boogers, bad dancing. But my stepmother didn’t want to be seen dying, and my father didn’t want to be seen losing it.

Dr. Alex Lopez is a stoic, coolly analytical genius whom I’ve never known well. By the time he was twenty-seven—when I was six years old—he was already a university professor of psychology and Mexican-American studies. Even then, he had salt-and-pepper hair, thick glasses, and an erect bearing so that from my earliest memories he had the appearance of unquestionable intellectual authority. My father’s booming baritone and biting sarcasm have always driven the saliva right out of my mouth. I feel destined to forever make silly remarks that result in eye rolling as my brilliant father explains the error of my thinking.

When I was a child, the only way he felt comfortable showing affection was by tickling me until I giggled so hard I couldn’t breathe, or by calling me pet names like fatso, ugly, and dingbat, followed by more tickling, apparently to assure me these weren’t insults but endearments. Even though I hated it, I learned to laugh, because it was the only time my daddy laughed with me.

My parents divorced when I was two. My mother feared she couldn’t raise me alone, and then she married a man who didn’t want stepchildren. So I spent most of my childhood with my father’s parents. Actually, I spent most of my childhood being tossed around like a hot potato.

The first two times Daddy remarried—when I was four, and again when I was seven—I temporarily moved out of my grandparents’ house to move in with him and each new “Mommy” as he attempted to draw a new family circle. Only on weekends and in the summers was I allowed to stay with the family I knew: Grampa, who built a loft bed in my bedroom and taught me to roller skate by pulling me around the driveway with a broomstick, and “Mom,” who listened to me read Dr. Seuss books while I sat on her lap and watched old Judy Garland movies with me on TV. Every Sunday night, when my grandparents brought me back to Daddy’s, I cried myself to sleep.

On weeknights, when Daddy and Step-Mommy Number Two worked late and couldn’t find a babysitter, I stayed home alone. One night when I was seven, I watched Steven Spielberg’s Duel on TV. I was terrified to go to sleep for fear a stranger would come in and try to kill me like the crazy trucker who chased that poor man in the movie. When Daddy came home at midnight to find me sitting up in his bed still watching TV, he blew up.

“I was too scared to sleep,” I said, crying. “The noise makes me feel better.”

“Don’t lie to me! I know you just want any excuse to watch TV.”

He and Step-Mommy Number Two said that a lot: “Don’t lie to me!” Every day after school, “Mommy” would ask if I’d gotten in trouble again for talking in class. If the answer was yes, she’d pull down my panties and spank my bare butt red; if the answer was no, she’d say, “Don’t lie to me!” pull down my panties and spank my bare butt red. That divorce was a relief.

Age nine: I lived with Dad’s girlfriend while he worked a second job and lived alone in his apartment. Age ten: I moved in with his girlfriend’s parents. I spent a lot of time with her mother, who spoke only Spanish. I only understood a few phrases, which made me feel frustrated and isolated. But she smiled a lot, made me homemade tortillas, and shook her head at my dad when he yelled at me, so I understood she was my friend. That didn’t last either. One Sunday night when I was eleven, I lay in bed listening to Daddy and Grampa shout in the living room. A week later I was happily living with my grandparents again.

I suppose another child would have figured out by then that happiness never lasts. When I was twelve, Grampa left. That same year, my mother disappeared—my real mother.

You know the old joke: my parents moved and didn’t tell me? From age five until age ten, I used to fly to Phoenix to stay with my mother and her husband for two weeks every summer. When I was eleven, they divorced and she returned to Southern California, where I saw her more often—for a while. When I was twelve, on Mother�

��s Day, I phoned to tell her I had a gift for her. A recorded voice informed me that her number was “disconnected or no longer in service.”

Hoping it was a mistake, I called the number for weeks. All that summer, the gift I’d bought her sat atop a bookshelf, waiting: a tiny cactus planted in a clear plastic pot, featuring a fluorescent colored sand painting of a palm tree. One day, a friend of mine accidentally knocked it over, and the orange, green, and pink sand spilled out. I carefully poured the grains back into the pot, but the sand painting had erased and I couldn’t recreate it. I stared at the blurred lines in the sand and started to cry, because I knew at that moment that my mother wasn’t coming back.

I grew determined to hang onto my grandmother, the woman I’d always called “Mom,” before, during, and between the rest.

By then my dad had become, not a Sunday father, but a birthdays and holidays father. In school, I earned mostly A’s, but Dad only noticed when I got a B. He didn’t get angry, just asked, “What happened?” When he visited Mom and me the Christmas of my sophomore year, I proudly showed him a report card with three A-pluses and two A’s. He absently said, “That’s nice,” and changed the subject. Hardly the opening of the heavens I’d busted my ass for. With the absurd logic of an angst-addicted teen, I chose a new approach: I’ll show you, I’ll screw me.

By the time I graduated I’d earned several C’s, a D, and an F, gotten stupid drunk and crazy stoned on multiple occasions, had sex (with a man I loved, of course) in my grandmother’s bathroom while she napped in the next room, and had an abortion at fifteen. It was easy to hide these things, because my grandmother was always working or sleeping and my father rarely visited.

To his credit, for graduation Dad gave me a much-undeserved car, a vintage VW bug. I accepted it and confessed nothing, believing it was a pittance compared to the blood he owed me.

On my sixteenth birthday, I began applying for work. Two weeks later, it was Father’s Day. I still hadn’t landed a job, so I bought dad’s gift with my allowance. When he opened the box and saw the tie clip, his jaw twitched with rage. I was shocked when he thrust the box back at me, saying it was time I got a job and he didn’t want any gift from me that I hadn’t paid for with money I’d earned.

“But Cara did earn that money, by doing chores,” my grandmother said.

“Mom, she shouldn’t be paid for housework. That’s an expected part of being a member of a family. Look, I don’t want to hear from Cara again until she’s found a job.” With that, he stalked out of the house, before I could remind him that it had only been two weeks since I’d reached the legal age to work, before I could explain that I’d applied for two dozen jobs and simply hadn’t been hired yet, before I could ask if he thought homemakers deserved a share of the family income, since housework was “an expected part of being a member of a family.”

By the time my dad married Christina, I was seventeen and beyond the desire to name another stranger “Mommy,” especially one as close to my age as she was to my dad’s. Christina was a twenty-six-year-old Mexican beauty just shy of a bachelor’s degree (which my father encouraged her to finish). She had dark, Siamese cat eyes and a girlish giggle that sounded like music to those she loved and an automatic weapon to those she suspected were fools. I never heard the music.

Christina hated me. I’ll admit by that point there wasn’t much to like. I was an embittered, self-centered, self-righteous teenager who spent most nights hanging out with my friends at a coffee shop until three a.m. We were actors and musicians, and we spent hours discussing how to save the world through art. When I told Christina that I planned to be an actress, she aimed her giggle weapon at me and fired sharp machine gun bursts of titters.

When I started attending my father’s university, she accused me of being ashamed of my Hispanic heritage since I refused to use Dad’s last name, Lopez. This wasn’t true; it wasn’t my heritage I was rejecting, but the father who had rejected me. My grandfather, my dad’s step-dad, had the last name Lee, and I used that name because I considered him my father. I didn’t explain this to Christina, sure it would only make her hate me more.

When I was nineteen, at Thanksgiving, Christina made her first overture of friendship in two years. She suggested we make tamales together on Christmas Eve. Equal parts excited and terrified at the prospect of spending time alone with her—in the kitchen, no less, where she was an undisputed master of the art of Mexican cooking and I felt like a klutz—I accepted.

Then, during the month before Christmas, I had what used to be called a nervous breakdown. Today you’d call it depression, although nervous breakdown sounds more like it felt: as if every nerve in my body had broken down. Nobody noticed.

It started shortly before Thanksgiving, when I got suspended from my waitress job because too many of my customers walked out without paying. Then my roommate moved out and I couldn’t find a new one. All I had in the fridge was a package of bologna and a carton of milk. Then my car broke down and I couldn’t afford the repairs. I was a commuting student and didn’t know anyone who could give me a ride. All this during my first semester attending the university where my father not only had a lofty reputation, but the power to crush my will: “Do you know what the odds are of making it in the film industry? Who’s going to hire a philosophy major? What do you mean ‘communications’?” Broke and jobless, without a ride or roommate, powerless and invisible, I withdrew for the semester and moved back in with my grandmother.

That’s when my birth mother called. Her only comment about the missing seven years: “I heard you’ve been looking for me.”

My two grandmothers had recently exchanged letters on the subject of my mother’s disappearance, and my mother’s mother had only this to say about the reason: “Jennifer said she called Cara one day, and Cara was in a hurry to rush off with some friends. Jennifer said she realized her daughter had her own life now and didn’t need a mother anymore.” Her twelve-year-old-daughter. That’s why, when my mother finally called and we made plans to get together, I was afraid to ask for explanations or voice recriminations, lest I scare her off again.

She took me shopping and bought me decadent amounts of clothing. We looked at each other in dressing room mirrors, each trying to find a glimpse of herself in the person standing next to her. At forty-one, my mother’s pale, freckled European-American beauty was still youthful, although the shiny dark hair she still piled on her head in a 1960s hairdo was streaked with gray, and her hazel eyes darted around nervously—as if she didn’t trust the world around her to remain constant. Our conversation rose and fell, from non-stop laughing chatter to nervous silence. As I moved in and out of fitting rooms, we tried to fill each other in on the last seven years of our lives. I was in love with a twenty-two-year-old business major I’d been dating for a year. She’d married her third husband, an engineer, four years before.

Shortly after our visit, the engineer called, crying, to tell me that my mother had become an alcoholic and that he thought I was a key to solving her problem. I tried to sympathize, but I began to wish my mother had stayed “disconnected or no longer in service.” This woman had never taken responsibility for me, and now I was supposed to help her? She and I briefly talked about it, and she explained that her husband’s emotional abuse had driven her to drink. By silent agreement, we treated her drinking the way we treated her disappearance: we acted as if it never happened.

Shortly after that, my boyfriend dumped me. He said I was too needy. Years later he confessed he was so high on cocaine during our relationship that he didn’t remember most of it.

At that point, although I continued to work sporadic temp jobs, I spent the bulk of my time in a sleepwalking triangle: from bed, to fridge, to TV, and back again. One day a couple of friends came over, and my grandmother sent them to my room to coax me out. They found me lying in bed shredding the pair of nylons I was wearing; I’d started pulling on a runner and gotten carried

away. I looked up sheepishly from the frayed nest of tan thread spread around me and we all laughed. Maybe if I hadn’t laughed someone would have noticed I was unraveling.

So you see, I kind of forgot about Christina’s tamales. In my defense, I will say she didn’t mention them for weeks.

I was surprised, the night before Christmas Eve, when I came home from a party after midnight to find a note in my grandmother’s angry handwriting. My friends used to joke that I had the only mom who knew how to yell in a note, with furiously dark scribbling, underlines, and exclamation points. The note said, “Christina and your dad called and they said to show up at their house at 9:00 a.m. sharp tomorrow morning, or don’t bother coming at all!”

I was incensed at this rude demand that presumed I had no other life beyond the one my occasional family ordered. I had plans. In an effort to rejoin the world, I was baking Christmas cookies in the morning to take to friends, including my estranged boyfriend, and I’d already called to tell everyone I was making rounds. So I decided to take Christina and my dad up on the “don’t bother coming at all” part of the message. If it was a joke, it obviously meant that it was okay to show up anytime. If it was serious, screw them!

On Christmas Eve day, after burning the cookies and getting burned by the ex—he loved the cookies, but not me anymore—when I showed up at Dad’s house he ran outside and met me at the car to tell me Christina was furious. I tried to explain my take on their note, but it sounded kind of stupid once I said it out loud. He “strongly suggested” I apologize.

If I was terrified of Christina before, now I could barely breathe. It was a long walk up the stairway to their Spanish style house with the antique terra cotta roof—my dad once told me those tiles weighed several tons. Inside, my heels echoed on the wood floor as I made my way to the kitchen, where Christina was stirring something on the stove.

They Only Eat Their Husbands

They Only Eat Their Husbands