- Home

- Cara Lopez Lee

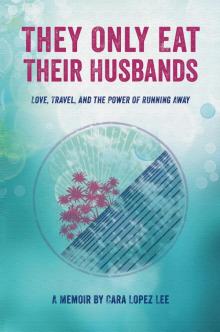

They Only Eat Their Husbands Page 8

They Only Eat Their Husbands Read online

Page 8

“Excuse me, Christina,” I said, and hesitated.

“Yes?” She turned to me. Ice chips flecked her eyes.

“I just wanted to say I’m sorry . . . ” I’d planned to say more, but my own sobs caught me by complete surprise, a wet and gasping implosion that hit with the ferocity of an asthma attack. I thought about the boyfriend who’d dumped me, the mother who’d dumped me, the restaurant customers who’d walked out on those checks, and the parade of stepmothers who’d walked in and out of my life. I wanted to tell her all that had happened in a few weeks. I wanted to say that her message had given me the feeling she didn’t want me there. I wanted to say I was terrified of women. But I couldn’t explain anything, because likely she would tell me I’d brought it all on myself, and because, worst of all, maybe I had. So instead of spewing the effluvia of nineteen years of emotional exile and self-pity, I only cried . . . and cried, and cried, until, in a voice cracked and dry as a desert, I came up with the empty explanation: “I’m sorry, I had a bad day.”

She put her arms around me and awkwardly patted my shoulder, carefully holding her body away from mine, so that at first glance someone might have thought we were demonstrating proper frame for a ballroom dance. Then she said, in a voice thick with irritation, “All right, Cara, all right. Don’t torture yourself. It’s okay.”

For the next few hours, the house filled with the tension of a battlefield during a ceasefire. After dinner, I offered to help Christina wash dishes, but she refused. So I sat in the breakfast nook with my dad and grandmother, while my stepmother attacked the dinnerware.

As she furiously scrubbed a pot, my father asked, “Christina, is something wrong?”

She thrust the pot into the suds as if she wished to drown it, and said, “I’m just tired of this game Cara’s playing with me.”

Sensing I was about to be as thoroughly scoured as that little pot, I wanted to run. But I was trapped. “Come on, Mom,” my dad said to my grandmother, as he rose from the table. “We should leave these two alone.” Silently, with a look over her shoulder at me, a look I couldn’t read, my grandmother followed her son out of the room. As Christina sat across from me, I felt a deep lethargy. There was no room inside me for any more pain.

She explained that her invitation had been a gesture of friendship, and that my not showing up felt like a slap in the face. I explained that I had shown up, after I’d kept my other commitments, and that her ultimatum “or don’t bother coming at all” felt like a slap in my face.

“Cara, I meant that as a joke.”

“If it was a joke, why did you expect me to respond to it like a command?”

The bottom line was we didn’t trust each other. I’d spoiled her fantasy about two women sharing a Mexican Christmas tradition. The significance was lost on me, because I had no memories of bonding with a woman in a kitchen. And, having only one foot in the world of Mexican culture, I didn’t understand how difficult tamales were to make, so I didn’t know why she needed more than a couple of hours of my help.

“I don’t buy that,” she said. “I think you left me high and dry to prove a point. You haven’t wanted me around from the beginning.”

Her comment took me by surprise. “I’ve always seen it the other way around. But okay, maybe I have seemed a little unapproachable. You have to understand, it’s not easy for me to get close to women. My dad’s been married a few times, and each time I believed that person was going to be my mother, and then she was gone. So, maybe I’m just a little cautious, you know?”

“Cara!” her thin voice sliced through the air, “I have no plans to be just another of your father’s wives. I’m here to stay, so get used to it.”

“I didn’t mean it that way . . . ” I felt the tears rising again, but they only enraged her more, because she saw them as part of my “game.”

The only thing that ended the argument was the stroke of midnight, when Christina declared a truce because it was time to open presents. At midnight every Christmas Eve, my family traditionally opens one gift each. So we gathered around the tree in the living room, where my grandmother and father ripped into their gifts and self-consciously extolled the contents, while Christina and I carefully peeled away paper and muttered wooden thank-yous. I don’t remember what my gift was. Shortly after one a.m., we all went to bed.

I lay awake on the fold-out couch in the den, listening to the familiar hum of L.A. traffic in the city below, staring up at the ceiling of this house in which I’d never lived, and imagining what it would be like if the tons of antique tile on the roof crashed through the ceiling and crushed us all. I realized that, if Christina had been wrong before, she was right now: I hoped she would leave him, like the others had. My body shook with cold, although the house was warm. This aching cold felt like hatred, and it frightened me. I tried to tell myself it was just a misunderstanding, but I couldn’t stop the waves of resentment. I knew I’d have to do everything I could to hide my feelings, or risk being skewered again by her thin, girlish anger.

Over the years, I tried to make peace with her. My grandmother suggested that asking people for advice was a good way to win them over. So I often called Christina for advice about school and career, friendships and men. She gradually responded and we developed a grudging friendship. I found most of her advice lacking in perception, but not for lack of effort. She was an intelligent, emotional woman, who cared deeply for her other family members, but, like many people, she lacked the imagination to empathize with someone to whom she felt no connection.

My grandmother thought it was simpler than that. She believed Christina was jealous because I was a reminder that my dad had once fathered a child with another woman. Christina had tried to have a baby for years, but couldn’t. Whatever the reasons, the tension remained.

Then, when she was forty-four, after she’d given up hope, Christina had a baby. Almost instantly, her attitude toward me softened. For the first time in years, she gave me a direct invitation to visit. I immediately took her up on it. I flew to L.A. as often as possible, not wanting to miss out on having a sister after thirty-three years as an only child. During those visits, Christina was so overflowing with love for her baby that she couldn’t help splashing me with some of the excess affection. It was like jogging past a cold sprinkler on a hot day, a refreshing shock.

The second time I visited, when Iliana was a few months old, her mother told me, “Your sister just loves music. Watch this.” She played a classical CD, and Iliana went quiet with elfin-eyed wonder. I picked up my sister and danced with her, and she smiled at me as we swayed around the floor. Love is a moment, like a pebble skipping across a pond. Iliana and I could not yet speak to each other, but it didn’t matter. It didn’t matter at all.

The third time I visited, my father said Christina had the flu and felt too sick to come out of her room. However, my grandfather stopped by. Although I didn’t know it then, Christina had invited him over to see me.

I hadn’t spoken to Grampa in years. This wasn’t my choice. When he’d married his second wife, he’d never given me his phone number. Even after they’d divorced, he’d rarely responded to my letters or calls. During this unexpected visit, he admitted that Christina had scolded him for neglecting me. He later explained that he’d stepped aside to give me a chance to bond with my dad, never realizing that he was depriving me of the only father I truly knew. I never had a chance to tell Christina how grateful I was to her, for giving that father back to me.

I still didn’t know she had cancer.

When Dad divulged her secret, first I pitied her, then I felt guilty, then I grew angry. Over the years she’d often accused me of being dishonest, of playing games, yet she’d spent nine years hiding the truth. And, because she wanted to maintain her lie, she left me stuck with the role of the biggest bitch in her life, and she in mine, even though those roles, too, were lies.

***

I can still smell the antiseptics and urine of the ICU, that halfway house of death. As Dad and I entered, my eyes scanned the beds, pausing at the sad sight of a tiny, shriveled, bald old man of about eighty, body twisted, arms twitching. That was the patient we approached. That little old man was Christina. As a reporter, I’d often seen the results of sudden, violent death. But nothing prepared me for the shock of sitting idle for two weeks, watching someone undergo a slow attack from within.

I told her I loved her, possibly the strangest truth of my life. If she weren’t in a coma, perhaps she would have sat up to accuse me of falsehood one last time. I promised to look out for her daughter.

Christina never spoke, yet in my memory she whispers: “I was only forty-six. I had a two-year-old daughter. I didn’t get to finish anything. I wasn’t ready. I wasn’t ready at all.” For me, forty-six is eleven years away. I know there’s no point in dwelling on death, which could come tomorrow, or sixty-five years from now. But whenever it comes, I don’t want it to catch me waiting for my life to turn out. That was Christina’s final gift to me, her unuttered advice, which for once I would follow. She convinced me not to wait any longer to do what I do best: run for it.

Some people say the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. Other people call this persistence. Then again, there are some things that seem the same, but when you look closely, they aren’t alike at all.

***

I arrived at my father’s house tonight in the gloom of a warm and smoggy L.A. evening. My dad, baby sister, and I hovered in the doorway, smiling and embracing, our faces dressed up in the family joy people wear for photos. “But what are those grinning people thinking about, really?” you might ask, trying to spot the flaw in this American portrait.

The wood floors squeaked as we walked through the dining room, past the table littered with bills, where Christina’s name stared belatedly from the little plastic windows of several envelopes. In the kitchen, the housekeeper had left two pots warming on the stove, organic beans and rice, macrobiotic fare the family had learned to eat in hopes of driving out the cancer in their midst. The patient was gone, but the diet remained, to beat back death for the survivors. Dad steamed organic vegetables and heated organic tortillas, and we all sat down to dinner in the breakfast nook where I’d once argued with Christina until midnight on a Christmas Eve.

While I helped my sister smear her mouth with bean drippings, I told my Dad about the high points of my road trip down the coast. When I spoke of the Hearst Castle, just outside San Luis Obispo, he smiled and said, “Christina and I went there once. She really enjoyed it. We took tour number one, but we talked about going back sometime and taking one of the other tours . . . ” He trailed off. Usually I feel a compulsion to fill dead air, but this time I let it die.

My dad interrupted the chewing session to ask if I’d take Iliana to preschool in the morning. I readily agreed, relieved to have a task, to feel I’m earning my keep. I’ve touted this three-month visit to my father as mutually beneficial: I’ll have a place to stay while planning the rest of my trip, and Dad and Iliana will have someone to fill in the blanks during a difficult transition. Yet, in spite of my good intentions, I feel like an interloper in this house of mourning.

After dinner, I watched Iliana play with the Russian nesting doll I bought her in Sitka. She made quite a show of unscrewing the top off each doll, eyes twinkling, as if she were about to show me a bit of magic. As she opened each one, she drew her mouth into a small round “o” and repeated, “There’s more!”

I certainly hope so.

***

I offered to shop for Iliana’s Halloween costume, but Dad said she had one. Last night I put it on her—a smiling, gap-toothed jack-o’-lantern. She looked even tinier in that puffy balloon of orange fabric, a monstrous mouth swallowing her middle, a fat green stem atop her little head.

Dad said, “Christina bought her that costume, before . . . ”

“Oh . . . It’s adorable,” I said, pretending to be at ease with these creepy pauses.

Before we left the house, I took a photo of my sister with our dad. He stared into space, while she stared into the lens with a puzzled look. Perhaps she was wondering what it is he’s always staring at, off in the middle distance.

Rather than take her trick-or-treating, which would have been about as fun as a funeral march, we took her to a party. In spite of the horde of sugar-rushing kids, it still felt like a wake. The presence of several small ghosts, angels, and skeletons did little to dispel the feeling.

The hosts served dinner as well as sweets, and Iliana asked to try my lemon garnish. I hesitated, but Dad said, “Let her try it. That’ll cure her curiosity.” Her comical pucker was followed by a look of delight and the sweet peal of giggles. “More!” she said. So I gave her another. “You’ve gotta love a kid who loves lemons,” I said to Dad. But he was staring at his favorite ghost again, who was missing another of her daughter’s firsts.

After dinner, the room became a headachy blur of orange cupcakes, miniature candies, and screaming children. I made Iliana a plate of goodies, and Dad and I stared as she turned her cupcake upside down, smeared frosting on her plate, and accidentally tipped over her punch. He angrily grabbed her arm, causing her to drop the cupcake on the ground as her eyes opened wide in terror. “Iliana! Why are you doing that?!” he shouted, inches from her face.

Tears rose in her eyes, while my heart leapt into my throat. I pulled her away from him and onto my lap. “She doesn’t know why she’s doing it, Dad!” I said. “She’s doing it because she’s two. Chill out!”

“All right.”

“Think about how big your voice is, and how little she is! You scared the hell out of her.”

“Okay. I get it.”

“Jesus,” I muttered. “You even scared me.”

“I said okay, Iliana! Drop it. Why do you have to drag everything out?”

“Dad, I’m not Iliana. I’m Cara.”

I looked around to see if anyone was watching. But the party roared on, unconcerned with our petty problems. I picked up my sniffling sister. “That’s okay. It was an accident. Would you like another cupcake?” She gave me a hesitant nod, and I carried her to the table of goodies. A moment later she was laughing, but my heart was still slamming up into my windpipe.

As I contemplated my emotionally crippled father, I began to fear that history will repeat itself, that he’ll abandon another daughter to be raised by relatives, that another girl will grow up feeling unwanted.

The Last Frontier

thirty-one years old

Sitting in the passenger seat of Chance’s Toyota Land Cruiser, I looked in the rearview mirror at Autumn and wondered why her friendly, gap-toothed smile made me nervous. The insubstantial but tempting warmth of Alaska’s Indian summer had convinced Chance to plan an overnight camping trip at Kenai Lake. Autumn and two of her three sons, ages six and eight, went with us.

A few months before he’d met me, Chance had met Autumn through a multi-level marketing group. They’d become instant friends. Her upbringing with a single father and three brothers had given her an affinity for male company. She was a young, conservative Christian, whose opinions seemed mostly borrowed; the most biting commentary I ever heard her attempt was when she gave Jane Fonda the pithy nickname “Communist Woman.” Although she wasn’t a woman of broad information, she was witty, vivacious, and full of infectious laughter. Of Athabascan descent, she had high cheekbones, deep brown eyes, and cinnamon skin. Depending on the light and her mood, her face might look grey-shadowed and plain, or glowing and goddess-like.

Her husband had said he’d try to join us, but he never showed. Mike worked long hours in construction and preferred to end his days in front of the TV. He didn’t approve of his wife’s good-looking male friends, loud female friends, or the multi-level marketing coho

rts who coaxed her into “gallivanting” at night. I suspected he was the blanket that had smothered Autumn’s opinions before they’d had a chance to breathe. However, the few times we saw them together he was so quiet it was easy to forget he was there, except for his rare wisecracks. Once, when Autumn wasn’t around, Mike joked about marrying her to make an honest woman of her. The look in his eyes, and the three children they’d had by their mid-twenties, lent truth to his jest. I thought the joke in poor taste and felt a little sorry for her.

I might have felt more sorry for her, except I could tell that Chance did, too.

At the lake, I grew increasingly jealous of Chance’s attentions to Autumn. First he helped her set up her tent. Very thoughtful. Then they both insisted I relax while they made dinner. I clenched my jaw as they giggled over the near-conflagration they started while lighting the camp stove. After dinner, Chance invited her for an evening float on the lake in his new inflatable boat, just the two of them. I stayed onshore to watch the kids. I could hear Chance and Autumn’s giggles echoing off the water, although I couldn’t see them through the trees lining the shore.

Her boys had crawled into their tent to sleep, but after the first half-hour, the six-year-old started calling for his mother. I peeked in and told him she was still in the boat.

“Are you cold?” I asked. “Do you need another blanket?”

“I want my mom.”

“I’m sorry. I’m sure she’ll be back soon.”

When they came back, I addressed Autumn in the flattest tone I could muster. “Your son was asking for you.”

She ran to the tent.

“How long were we gone?” Chance asked.

“About an hour.”

They Only Eat Their Husbands

They Only Eat Their Husbands